| Riferimento: | S48449 |

| Autore | Anonimo |

| Anno: | 1545 ca. |

| Misure: | 395 x 280 mm |

| Riferimento: | S48449 |

| Autore | Anonimo |

| Anno: | 1545 ca. |

| Misure: | 395 x 280 mm |

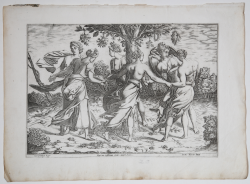

La danza delle driadi: sei donne drappeggiate che danzano intorno a una quercia.

Bulino 1540/45 circa, con iscrizione in latino e nome del disegnatore.

Deriva dall'incisione di Pierre Milan, su disegno di Rosso Fiorentino.

Il disegno di Rosso è stato affrescato in un piccolo cartiglio sotto una delle grandi scene della Galerie di Fontainebleau. Il soggetto è tratto dalle Metamorfosi (VIII 738-884) di Ovidio: le driadi proteggono l'albero minacciato da Erysichthon.

Si tratta di una replica del soggetto, anonima, di un incisore italiano o francese stampata a Roma dalla tipografia Lafreri, come dimostra anche la filigrana di questo esemplare, la “sirena in cerchio sotto stella a sei punte” (Woodward nn- 91-92, la data dal 1557 al 1570).

Un esemplare di questa incisione, stampata su carta blu, è conservato alla National Gallery of Art di Washington.

https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.56209.html

Sull’opera di Pierre Milan così scrive David Acton: “One of the few plates solidly attributed to Milan, this engraving clearly exemplifies the craftsman's technique and provides clues to his relationship with Rosso Fiorentino. Giorgio Vasari mentioned the print in his biography of Rosso, but he believed that René Boyvin was the engraver. The image is based on a design used for a secondary fresco in the Gallery of Francis I at Fontainebleau: a medallion located beneath the fresco The Sacrifice in the westernmost compartment on the north side of the gallery. The painting represents only the figures, lacking the tree or any indication of landscape, and thus appears as a more generic dance scene. There is a drawing of the complete composition, which seems to be a close copy of Rosso's original (Paris, Ecole des Beaux-Arts inv. no. Masson 811). Zerner suggested that this may have been an intermediary drawing after Rosso's original, used by the printmaker. The inscription identifies the subject of this image as the rite of nymphs who dwelt in the forests, fields, and orchards, devotees of the nature goddess Ceres. Dryads were wood nymphs who embodied the spirits of trees, especially oaks. It was believed that the lives of some of these creatures, the Hamadryads, began and ended with those of the trees they inhabited. In his telling of this legend Ovid described a towering oak that stood in Ceres' sacred grove (Metamorphoses 8.738-884). Centuries old, the magic tree had a girth of fifteen ells and had been an object of devotion from earliest times. Worshipers whose prayers were granted hung its branches with votive offerings of colored yarn, clay tablets, and floral wreaths. The dryads held ritual dances around this oak, which stood in Thessaly, an area ruled by the evil king Erysichthon. This monarch resented the worship of Ceres. Resolved to desecrate her natural shrine, he ordered that the great oak be felled. When his servants refused, the king took up the ax himself. At his first blow the tree's leaves grew pallid, blood flowed from its trunk, and the voice of its spirit rang out in a curse. Even this miracle did not deter him, and he chopped the tree to the ground. When Ceres heard of the crime, she decided on a horrible punishment. The goddess commanded Famine to haunt Erysichthon, so that he would starve no matter how much he ate. He spent his vast fortune on quantities of unsatisfying food and even sold his daughter into slavery to buy more. Finally the king turned on himself and literally devoured his own body. Milan's engraving represents the nymphs' happy celebration before the infamous desecration. Six dryads dance around the oak, which is laden with ex-votos as well as acorns. Flowers and branches of laurel are strewn on the ground, bare of undergrowth from years of circumambulation. In contrast to the bright clearing, the distant forest appears dense and dark. A vine of ivy spirals around the tree trunk like a ribbon round a maypole, echoing the circular movement of the dryads' dance. The vine symbolizes the intimate association between the dryads and the trees. This motif is repeated in the coiled tree in the background; bare and lifeless, it foreshadows the tragic events to come. Clad in loosely fitting chitons, the dancers have elegant coiffures bound atop their heads with fillets and ornamented with flower crowns and laurel. Swaths of drapery blow away from their bodies as if a breeze is passing through the scene from right to left, accenting their movement. The light also falls in this direction, casting shadows to the left of the figures and subtly implying the direction of their encircling dance. The viewer naturally identifies with the central nymph, who turns her back to us as she looks and skips to the right and into the wind. The staffage in this print, such as the lilies and roses scattered in the foreground, is close to details in Milan's other early prints. Technically this engraving represents Milan at the height of his powers. As in his other plates the engraver circumscribed his forms with an even line and then modeled the figures with overlaid passages of parallel and cross-hatching. In its regularity and relative openness Milan's manner would seem to have grown out of Gian Jacopo Caraglio's engraving style of about 1525, when that artisan made prints after Rosso's designs. At that time his hatching was not as dense as it was earlier, when he worked in a manner based closely on that of Marcantonio Raimondi. In the present print Milan's deeply carved lines are steady and confident, and their intervals even and regular. The modeling systems are so precise that some super-imposed networks of hatching read as moiré patterns. Milan's curved hatching follows the contours of the forms. Engraved lines of varied width suggest that he carved the plate with more than one burin. Although the painted medallion in the Gallery of Francis I does not include the tree, the fresco above it, The Sacrifice, shows an ancient ritual being cele-brated under a large oak. Thus Dora and Erwin Panofsky speculated that the trees central to both images might symbolize France and her ruling dynasty. Eugene Carroll suggested that The Sacrifice was modified and completed after the death of the dauphin and that changes in its imagery, which had implications for Dance of the Dryads, were meant to strengthen symbols of dynastic continuity". The fully realized composition of this engraving, and of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts drawing, certainly reflects Rosso's original design. Along with Milan's other engravings after his drawings, they imply that the craftsman may have been directly acquainted with the artist. Based on the placement of the dancing nymphs in the Gallery of Francis I, Carroll dated the design and the present print to about 1532-34." Although it now appears likely that Milan began making prints during the painter's lifetime, such a date for this engraving seems too early. A date closer to 1540 is more probable” (cfr. David Acton in The French renaissance in Prints' pp. 296-297).

Bella prova, impressa su carta vergata coeva con filigrana “sirena in cerchio sotto stella a sei punte” (Woodward nn- 91-92), con ampi margini, in eccellente stato di conservazione.

Bibliografia

Robert-Dumesnil, Le Peintre-Graveur Français (VIII.47.74.I); Zerner, Ecole de Fontainebleau. Gravures (PM.1); 'Rosso Fiorentino', Washington 1987, Cat. 89; The French renaissance in Prints', Los Angeles 1994, Cat. 70.

Anonimo

Anonimo