| Reference: | S35106 |

| Author | Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) |

| Year: | 1585 |

| Zone: | Algeri |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 522 x 393 mm |

| Reference: | S35106 |

| Author | Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) |

| Year: | 1585 |

| Zone: | Algeri |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 522 x 393 mm |

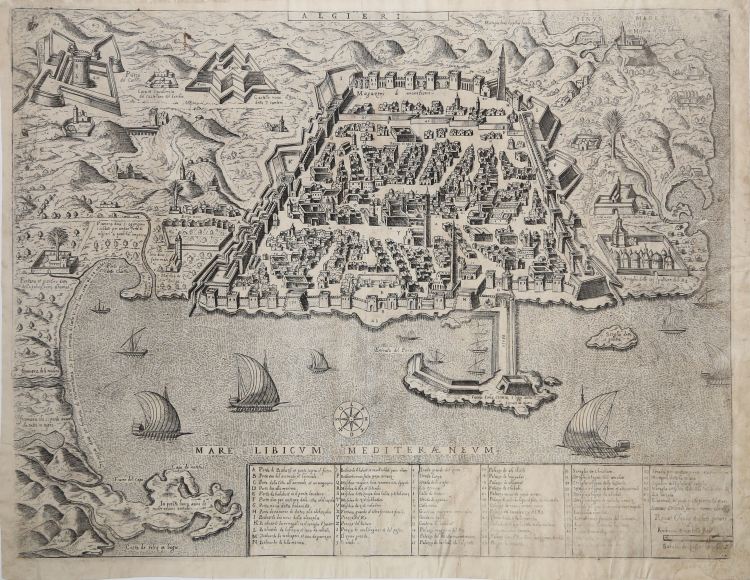

Extremely rare perspective map of the city, engraved by Ambrogio Brambilla for the publisher Claudio Duchetti. The first edition of the plate was published in 1585, while this example is from Giovanni Orlandi's 1602 edition.

At the top center, in a ribbon-shaped cartouche along the edge, we find the title: ALGIERI. An alphanumeric legend of 71 references (A-Z, 1-48) to notable places and monuments is engraved along the lower margin, distributed over six columns that are contained in as many boxes. In the last box on the right we find the editorial indications: Romae Claudij ducheti formis 1585. This is followed by the engraver's signature: Ambrosius Brambilla fecit. Also inside the last box is the Schala de passa trenta (equal to 18 mm). Orientation provided by a compass rose placed in the sea, the north-east is at the bottom. On the plate some captions provide historical-geographical information and there are further toponymic indications.

Based on the model by Alfonso Zuniga, the work could derive from the similar plan by Mario Cartaro (Rome, around 1580), of which it follows the alphanumeric legend of 71 references. This is the second plate of Algiers that Duchetti commissioned from Brambilla, probably because, following the hereditary division of the Lafreri plates, he lost possession of the first plate (1579). It was probably therefore simple commercial reasons that pushed Duchetti to create this replica. The copperplate was inherited by Giacomo Gherardi and is included in the catalogue drawn up for the widow Quintilia Lucidi (17-19 October 1598, no. 355) where it is described as “Algieri Reale”. The second edition of this version was edited by Giovanni Orlandi, who acquired the chalcographic collection from the heirs of Duchetti (1602).

Regarding the Zuniga model: “Si tratta di una grande pianta, stampata su quattro fogli uniti, pubblicata a Venezia nel 1573, con privilegio pontificio decennale, e privilegio ventennale del Senato di Venezia e di Alfonso a Stuniga. Il lungo cartiglio, che contiene la dedica a Filippo II di Spagna, esplicita che l’immagine di Algeri e quella disegnata da Ioannes Paciceus (it. Giovanni Pacheco), e accresciuta e corretta da Alfonsus a Stuniga (it. Alfonso Zuniga, o Zunica, Sunica, de Stuniga), Hispanus, ovvero spagnolo anche lui come Pacheco. Riguardo il Pacheco, presso l’Archivio di Stato di Mantova e conservato un interessante e prezioso documento: la lettera che Giovanni Pacheco, in data 6 ottobre 1571 invia al principe di Mantova Vincenzo Gonzaga, per accompagnare il dono dell’incisione di Algeri. La data, dunque, costituisce il terminus ante quem dell’opera. Non abbiamo reperito alcuna notizia circa Alfonso Zuniga. Presumiamo che appartenga alla famiglia Zunica che, originaria della Spagna, fu portata a Napoli nel 1514 da Cristofaro Zuniga. La famiglia nobiliare si divide poi in molti rami. Si ha notizia di un Alfonso Zuniga, capitano di cavalleria, che nel 1532 ottenne in dono il feudo di Pescomaggiore e di Felitto per aver sedato la rivolta dei cittadini aquilani contro gli spagnoli. (cfr. Candida Gonzaga, Memorie delle Famiglie Nobili delle Provincie Meridionali d’Italia, vol 2, p. 210; e P. Cavallo, La Storia dietro gli scudi, vol. 3 – s. v. Zunica). La veduta è molto ricca di dettagli e precisa nelle indicazioni; senza dubbio si tratta della rappresentazione più completa di Algeri del XVI secolo, non sorprende, quindi, che diventerà il modello iconografico di tutta la produzione successiva, da Duchetti-Brambilla, a Cartaro, a Florimi. Lo stesso modello, di formato ridotto, è pubblicato da Braun & Hogenberg nel secondo libro (1575) del Civitates Orbis Terrarum, che ricalca solo la rubrica in italiano. Monchicourt, che evidentemente non conosceva questa grande veduta dello Stunica, a proposito di Algeri di Braun & Hogenber, aveva avanzato l’ipotesi che questa - o un’altra pianta analoga - potesse essere uno dei due “disegni” di Algeri – “uno a mano, et l’altro stampato” - che i cavalieri Francesco Lanfreducci e Gian Ottone Bosio, dichiarano di aver utilizzato per il loro rapporto presentato al Gran Maestro di Malta nel 1587. Infatti, nessuno dei due aveva mai visitato Algeri, pertanto il rapporto, come da loro stessi dichiarato, era un’opera di compilazione basata a partire dai racconti dei prigionieri corredata da due piante che si trovavano allegate alla relazione, ma che sono andate smarrite. La città e rappresentata in forma di trapezio, con il lato più lungo parallelo alla linea di costa. Lungo gli altri tre lati, un fossato pieno d’acqua costeggia le mura interrotte, a intervalli regolari, da torri quadrate e, nei punti strategicamente più importanti, da bastioni a forma di cuneo. Dalla parte del mare si trovano il baluardo di Cochiaperi e quello della Marina. Ben visibili sono anche le porte turrite dell’arsenale, comprese tra questi due bastioni. Nell’agglomerato urbano, si distinguono cinque moschee. La qasba, Alcazaba, e rappresentata nella parte superiore della città, separata dal resto della città da un muro. Molto accurata e l’immagine del Palazzo del Re, e della rete viaria, coi nomi delle strade che si riferiscono alle varie attività commerciali esercitate” (cfr. Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e Topografia Italiana del XVI secolo, p. 476).

Good proof, printed on contemporary laid paper, slight restorations visible on the verso, otherwise in good condition.

A very rare map: only 3 institutional examples of the first issue are known: Chicago, Newberry Library; Malta, National Library; Parigi, Bibliothèque Nationale, while of this second state the only one copy is at Istituto Centrale per la Grafica.

Bibliografia

Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e Topografia Italiana del XVI secolo, p. 486, tav. 122 II/II; Ganado (1994): VI, n. 13; cfr. Pagani (2008): pp. 15, 374; cfr. Pagani (2011): p. 132; Pagani (2012): p. 82; Tooley (1983): n. 101a.

Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) (Attivo a Roma nella seconda metà del XVI sec.))

|

Print dealer and publisher.Active in Venice 1565-1572 and Rome.He was the brother of Francesco Duchetti and a nephew of Antonio Lafrery, inheriting half his plates.

Died 5 December 1585.He was buried in San Luigi dei Francesi.By the terms of his will, his brother –in-law Giacomo Gherardi was to run the business until the majority of Claudio’s son, Claudio.

While Gherardi in charge, he was to inscribe the prints ‘haeredes Claudii Duchetti’.

He commissioned plates from among others Perret, Thomassin and Brambilla.

The name 'Lafreri-School' is a widely used, but rather inaccurate, term used to describe a loose grouping of cartographers, mapmakers, engravers and publishers working in the twin centres of Rome and Venice, from about 1544 to circa 1585. Earlier this century, George Beans, a prominent American collector of Italian maps and atlases, proposed the alternative name 'I.A.T.O.' to describe the composite collections assembled and sold by this school - 'Italian, Assembled-To-Order'. While more apposite, it has failed to catch on with modern cataloguers and collectors. For the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to the cartographers, engravers and publishers involved as "the school", although even this term implies a greater structure and organisation than can currently be established. The principal reference source on the work of the school is R.V. Tooley's Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century (1). In his study, published in 1939, Tooley listed some 614 maps and plates (with variant states counted separately). Some were described from personal examination, others noted from secondary sources and listings. While now much out-dated, as more recent regional carto-bibliographies have effectively superceded particular sections, and new collections have come to light, it remains the only overview of the output of the school. The principal cartographer of the school was Giacomo Gastaldi (fl. 1542-1565), a Piedmontese who worked in Venice, becoming Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic. Karrow described him as "one of the most important cartographers of the sixteenth century. He was certainly the greatest Italian mapmaker of his age..." (2). While his achievement is obvious, it is hard to quantify. A large number of maps were published throughout this period with the geography credited to Gastaldi, but it is often difficult to know what role Gastaldi played in their creation. As a practice, he did not sign himself as publisher, although his name may be found in the title, dedication, or text to the reader. Frequently where there is no imprint one may assume that Gastaldi was the publisher. A further clue may be that many of the maps attributable to Gastaldi as publisher seem to have been engraved by Fabius Licinius. In other cases, where publication is credited to another, it is not always certain whether Gastaldi was commissioned by the publisher to compile the map, whether another less-enterprising publisher merely copied his work and attribution, or simply added Gastaldi's name in the title to add authority to the delineation. His name clearly commanded the same sort of respect that the Sanson name had in the last years of the seventeenth century, and as Guillaume de l'Isle's had in the first half of the eighteenth century. Paolo Forlani was a cartographer and engraver who worked in Venice between 1560 and circa 1571. The majority of his output was published under the imprint of other publishers, such as Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Ferrando Bertelli and Bolognini Zaltieri. In a pioneering study, David Woodward (4), by identifying Forlani's engraving style through various stages of development, has attributed a large number of previously unidentified maps to his hand, and provided a clearer picture of some of the publishing arrangements of the period. In the early 1560s Giovanni Francesco Camocio published a number of maps that were drawn by Forlani, including maps of the World, North Atlantic, Africa, France, Switzerland, and provinces of the Low Countries, to note but a few. Circa 1570, Camocio published an Isolario, or collection of maps of islands, principally from the Mediterranean, but including the British Isles and Iceland. Camocio's earliest issues lacked a title-page, and tended to be a relatively random selection from the available stock. Later he added a title Isole Famose Porti, Fortezze E Terre Maritime. After his death, which is assumed to have been in 1573, the plates were reprinted, with a title-page bearing the Bertelli family address 'alla Libraria del Segno di S. Marco', possibly by Donato Bertelli, whose imprint is found on a later state of Camocio's world map of 1560. The largest grouping was the Bertelli family. The most active was Ferrando Bertelli, who flourished in the 1560's and 1570's, but maps from the last quarter of the seventeenth century are known with the imprints of Andrea, Donato, Lucca, Nicolo and Pietro. Again, a number of maps published by Ferrando were drawn or engraved by Forlani.

Antonio Salamanca (1500 – 1562) settled in Rome his chalcographical business; his activity was then carried on and enlarged by his scholar Antonio Lafrery (1512 – 1577), and then by his grand son Claudio Duchet (Duchetti), Giovanni Orlandi, Henrik van Schoel, and finally by De Rossi. In Venice, the most important centre of map production, he was initiated into engraving by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore and Matteo Pagano, who had worked with Giacomo Gastaldi, the most important European cartographer of the XVI century. Other important exponents of the Venetian chalcography were Fabio Licinio, Fernando Bertelli, Giovanni Francesco Camocio and above all of them Paolo Forlani. Although he’s better known as publisher of Roman archeology, Antoine de Lafrery, born in France, has been the publisher thathas given the biggest impulse to Roman chalcography, becoming in a few years an expert seller as well. For that reason, even though he’s not the one that has published most maps in his time, all the chalcographic works printed in Rome and Venice during the XVI century are nowadays defined as “charts of lafrerian school”. This definition was given by Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, one of the fathers of the history of cartography, who also introduced the definition of Lafrery Atlas, talking about charts printed in Rome and published by Lafrery, in which we find a sort of title page with the title Tavole moderne de geografia secondo l’ordine di Tolomeo. Lafrery’s school produced a huge amount of maps, usually selling them as separate charts and somehow and then edited in a bigger volume. Since the charts had all different measures, the artists needed to trim them with copper to get them to the same size, adding at the end estra pieces of paper, if necessary.

|

Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) (Attivo a Roma nella seconda metà del XVI sec.))

|

Print dealer and publisher.Active in Venice 1565-1572 and Rome.He was the brother of Francesco Duchetti and a nephew of Antonio Lafrery, inheriting half his plates.

Died 5 December 1585.He was buried in San Luigi dei Francesi.By the terms of his will, his brother –in-law Giacomo Gherardi was to run the business until the majority of Claudio’s son, Claudio.

While Gherardi in charge, he was to inscribe the prints ‘haeredes Claudii Duchetti’.

He commissioned plates from among others Perret, Thomassin and Brambilla.

The name 'Lafreri-School' is a widely used, but rather inaccurate, term used to describe a loose grouping of cartographers, mapmakers, engravers and publishers working in the twin centres of Rome and Venice, from about 1544 to circa 1585. Earlier this century, George Beans, a prominent American collector of Italian maps and atlases, proposed the alternative name 'I.A.T.O.' to describe the composite collections assembled and sold by this school - 'Italian, Assembled-To-Order'. While more apposite, it has failed to catch on with modern cataloguers and collectors. For the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to the cartographers, engravers and publishers involved as "the school", although even this term implies a greater structure and organisation than can currently be established. The principal reference source on the work of the school is R.V. Tooley's Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century (1). In his study, published in 1939, Tooley listed some 614 maps and plates (with variant states counted separately). Some were described from personal examination, others noted from secondary sources and listings. While now much out-dated, as more recent regional carto-bibliographies have effectively superceded particular sections, and new collections have come to light, it remains the only overview of the output of the school. The principal cartographer of the school was Giacomo Gastaldi (fl. 1542-1565), a Piedmontese who worked in Venice, becoming Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic. Karrow described him as "one of the most important cartographers of the sixteenth century. He was certainly the greatest Italian mapmaker of his age..." (2). While his achievement is obvious, it is hard to quantify. A large number of maps were published throughout this period with the geography credited to Gastaldi, but it is often difficult to know what role Gastaldi played in their creation. As a practice, he did not sign himself as publisher, although his name may be found in the title, dedication, or text to the reader. Frequently where there is no imprint one may assume that Gastaldi was the publisher. A further clue may be that many of the maps attributable to Gastaldi as publisher seem to have been engraved by Fabius Licinius. In other cases, where publication is credited to another, it is not always certain whether Gastaldi was commissioned by the publisher to compile the map, whether another less-enterprising publisher merely copied his work and attribution, or simply added Gastaldi's name in the title to add authority to the delineation. His name clearly commanded the same sort of respect that the Sanson name had in the last years of the seventeenth century, and as Guillaume de l'Isle's had in the first half of the eighteenth century. Paolo Forlani was a cartographer and engraver who worked in Venice between 1560 and circa 1571. The majority of his output was published under the imprint of other publishers, such as Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Ferrando Bertelli and Bolognini Zaltieri. In a pioneering study, David Woodward (4), by identifying Forlani's engraving style through various stages of development, has attributed a large number of previously unidentified maps to his hand, and provided a clearer picture of some of the publishing arrangements of the period. In the early 1560s Giovanni Francesco Camocio published a number of maps that were drawn by Forlani, including maps of the World, North Atlantic, Africa, France, Switzerland, and provinces of the Low Countries, to note but a few. Circa 1570, Camocio published an Isolario, or collection of maps of islands, principally from the Mediterranean, but including the British Isles and Iceland. Camocio's earliest issues lacked a title-page, and tended to be a relatively random selection from the available stock. Later he added a title Isole Famose Porti, Fortezze E Terre Maritime. After his death, which is assumed to have been in 1573, the plates were reprinted, with a title-page bearing the Bertelli family address 'alla Libraria del Segno di S. Marco', possibly by Donato Bertelli, whose imprint is found on a later state of Camocio's world map of 1560. The largest grouping was the Bertelli family. The most active was Ferrando Bertelli, who flourished in the 1560's and 1570's, but maps from the last quarter of the seventeenth century are known with the imprints of Andrea, Donato, Lucca, Nicolo and Pietro. Again, a number of maps published by Ferrando were drawn or engraved by Forlani.

Antonio Salamanca (1500 – 1562) settled in Rome his chalcographical business; his activity was then carried on and enlarged by his scholar Antonio Lafrery (1512 – 1577), and then by his grand son Claudio Duchet (Duchetti), Giovanni Orlandi, Henrik van Schoel, and finally by De Rossi. In Venice, the most important centre of map production, he was initiated into engraving by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore and Matteo Pagano, who had worked with Giacomo Gastaldi, the most important European cartographer of the XVI century. Other important exponents of the Venetian chalcography were Fabio Licinio, Fernando Bertelli, Giovanni Francesco Camocio and above all of them Paolo Forlani. Although he’s better known as publisher of Roman archeology, Antoine de Lafrery, born in France, has been the publisher thathas given the biggest impulse to Roman chalcography, becoming in a few years an expert seller as well. For that reason, even though he’s not the one that has published most maps in his time, all the chalcographic works printed in Rome and Venice during the XVI century are nowadays defined as “charts of lafrerian school”. This definition was given by Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, one of the fathers of the history of cartography, who also introduced the definition of Lafrery Atlas, talking about charts printed in Rome and published by Lafrery, in which we find a sort of title page with the title Tavole moderne de geografia secondo l’ordine di Tolomeo. Lafrery’s school produced a huge amount of maps, usually selling them as separate charts and somehow and then edited in a bigger volume. Since the charts had all different measures, the artists needed to trim them with copper to get them to the same size, adding at the end estra pieces of paper, if necessary.

|