| Reference: | ms5755 |

| Author | Sebastian Münster |

| Year: | 1540 ca. |

| Zone: | Sri Lanka |

| Printed: | Basle |

| Measures: | 340 x 250 mm |

| Reference: | ms5755 |

| Author | Sebastian Münster |

| Year: | 1540 ca. |

| Zone: | Sri Lanka |

| Printed: | Basle |

| Measures: | 340 x 250 mm |

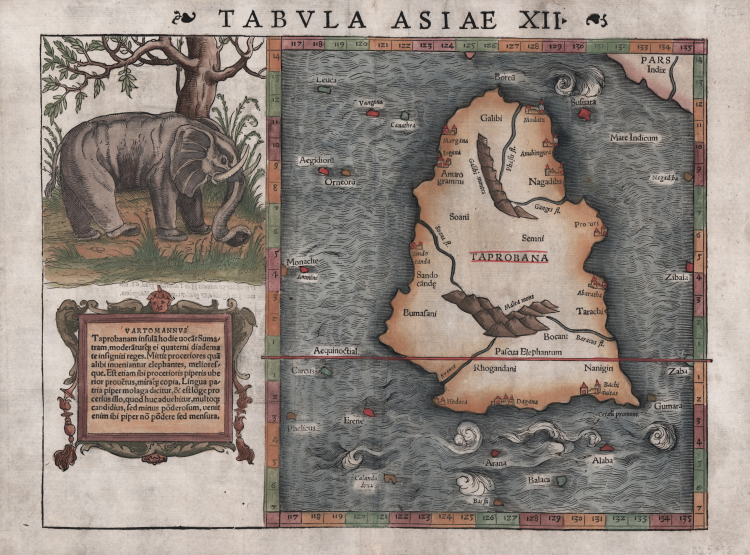

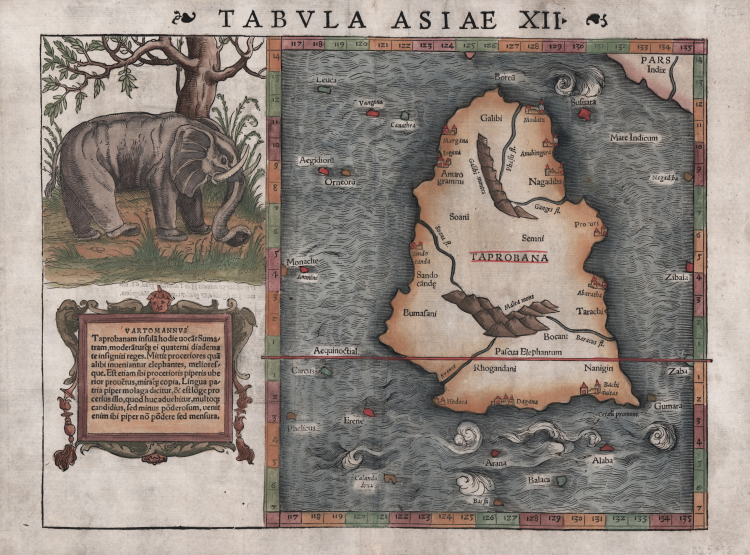

Finely colored example of Munster's map of Taprobana, the island of Ceylon, which was sometimes confused with Sumatra on early maps.

In the top left is a superb woodcut of the Pascua Elephantum (an elephant at pasture) which Ptolemy wrote in his Geographia, of seeing at the base of the Malli Mountains. In the lower left is a decorative cartouche which includes a note indicating that the island was a rich source of ivory. In ancient times, Sri Lanka was known by various names, Ptolemy named it Taprobana, the Arabs Serendib, the Portuguese called it Ceilo and the British Ceylon.

Situated at the centre of numerous trade routes through the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka was always an important trading link between east and west. As a major exporter of cinnamon, Arab and Chinese traders had frequented the island since early times and it served as an important stop for merchants on the maritime route between Asia and Europe. Much confusion existed among medieval mapmakers as to the identities of the islands of Taprobana and Sumatra which arose primarily from the descriptions in the ancient texts which stated that Taprobana was the largest island in the world. This was later contradicted by Marco Polo in his Il Milione in which he stated that it was Java Minor (Sumatra) that was in fact the largest island. As Sumatra was virtually unknown to most medieval mapmakers their primary concern was the placement of Taprobana on maps. Invariably it was incorrectly positioned off the southeast coast of Arabia but once the accounts of Marco Polo were revealed at the end of the thirteenth century, the eastern limits of the Indian Ocean were greatly expanded and the question as to the identity of the islands became more critical for mapmakers.

The Portuguese arrived on the island in 1505 and by 1518 had built a fort in Colombo, enabling them to control strategic coastal areas they had previously captured. Once Portuguese information and charts were copied, the position of Ceylon and the confusion with Sumatra was corrected.

Although, some scholars believe it is actually a depiction of the island of Sumatra. The surrounding islands are located near where Nias, Enggano and Mentawis are relative to Sumatra. The land in the upper-right corner is correct for Malaysia. Several towns and village are located (close to present cities of Lampung, Medan, Sibolga and Banda Aceh. Mountains and waterways are also located - also very near where they are found today.

Map taken from the Geographia universalis, vetus et nova, complectens. Claudii Ptolemaei Alexandrini Ennarationis libros VIII, published for the first time in 1540 in Basel by Heinrich Petri, stepson of Münster and his trusted printer.

The book is illustrated by 27 maps built following the indications of Ptolemy, which are flanked by 21 "modern" maps, outlined on the basis of recent geographical discoveries. The Geographia of Münster was a great success, and Petri reprinted it the following year (1541) and then in 1542..

Having increased the number of modern maps by six, including the Carta Marina of Olao Magnus describing Scandinavia, the publisher reprinted it again in 1545, in 1551 and finally in 1552, still with 54 maps, but with the substitution of Pomerania in place of Lake Constance. At the death of Münster the work was not reprinted; some of the maps were instead used by Heinrich Petri for the posthumous editions of the Cosmographiae Universalis. The woodblock of the maps, duly amended, were used for the Rerum Geographicarum of Strabo, edition printed in Basileae: Ex Officina Henricpetriana, 1571 Mense Augusto.

Woodcut with fine later hand colour, in very good condition.

References

Moreland p.82, 302, Parry p.65-67, Shirley p.76, Suarez (A) p.101.

Sebastian Münster (1488 - 1552)

|

Sebastian Münster was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and Hebrew scholar whose Cosmographia (1544; "Cosmography") was the earliest German description of the world and a major work - after the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 - in the revival of geography in the 16th-century Europe. Altogether, about 40 editions of the Cosmographia appeared during 1544-1628. Although other cosmographies predate Münster's, he is given first place in historical discussions of this sort of publication, and was a major influence on his subject for over 200 years.

In nearly all works by Münster, his Cosmographia is given pride of place. Despite this, we still lack a detailed survey of its contents from edition to edition, along the years from 1544 to 1628, and an account of its influence on a wide range of scientific disciplines. Münster obtained the material for his book in three ways. He used all available literary sources. He tried to obtain original manuscript material for description of the countryside and of villages and towns. Finally, he obtained further material on his travels (primarily in south-west Germany, Switzerland, and Alsace). The Cosmographia contained not only the latest maps and views of many well-known cities, but included an encyclopaedic amount of details about the known - and unknown - world and undoubtedly must have been one of the most widely read books of its time.

Aside from the well-known maps and views present in the Cosmographia, the text is thickly sprinkled with vigorous woodcuts: portraits of kings and princes, costumes and occupations, habits and customs, flora and fauna, monsters and horrors. The 1614 and 1628 editions of Cosmographia are divided into nine books. Nearly all the sections, especially those dealing with history, were enlarged. Descriptions were extended, additional places included, errors rectified.

|

Sebastian Münster (1488 - 1552)

|

Sebastian Münster was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and Hebrew scholar whose Cosmographia (1544; "Cosmography") was the earliest German description of the world and a major work - after the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 - in the revival of geography in the 16th-century Europe. Altogether, about 40 editions of the Cosmographia appeared during 1544-1628. Although other cosmographies predate Münster's, he is given first place in historical discussions of this sort of publication, and was a major influence on his subject for over 200 years.

In nearly all works by Münster, his Cosmographia is given pride of place. Despite this, we still lack a detailed survey of its contents from edition to edition, along the years from 1544 to 1628, and an account of its influence on a wide range of scientific disciplines. Münster obtained the material for his book in three ways. He used all available literary sources. He tried to obtain original manuscript material for description of the countryside and of villages and towns. Finally, he obtained further material on his travels (primarily in south-west Germany, Switzerland, and Alsace). The Cosmographia contained not only the latest maps and views of many well-known cities, but included an encyclopaedic amount of details about the known - and unknown - world and undoubtedly must have been one of the most widely read books of its time.

Aside from the well-known maps and views present in the Cosmographia, the text is thickly sprinkled with vigorous woodcuts: portraits of kings and princes, costumes and occupations, habits and customs, flora and fauna, monsters and horrors. The 1614 and 1628 editions of Cosmographia are divided into nine books. Nearly all the sections, especially those dealing with history, were enlarged. Descriptions were extended, additional places included, errors rectified.

|