| Reference: | S42612 |

| Author | Pablo PICASSO |

| Year: | 1956 |

| Measures: | 115 x 150 mm |

| Reference: | S42612 |

| Author | Pablo PICASSO |

| Year: | 1956 |

| Measures: | 115 x 150 mm |

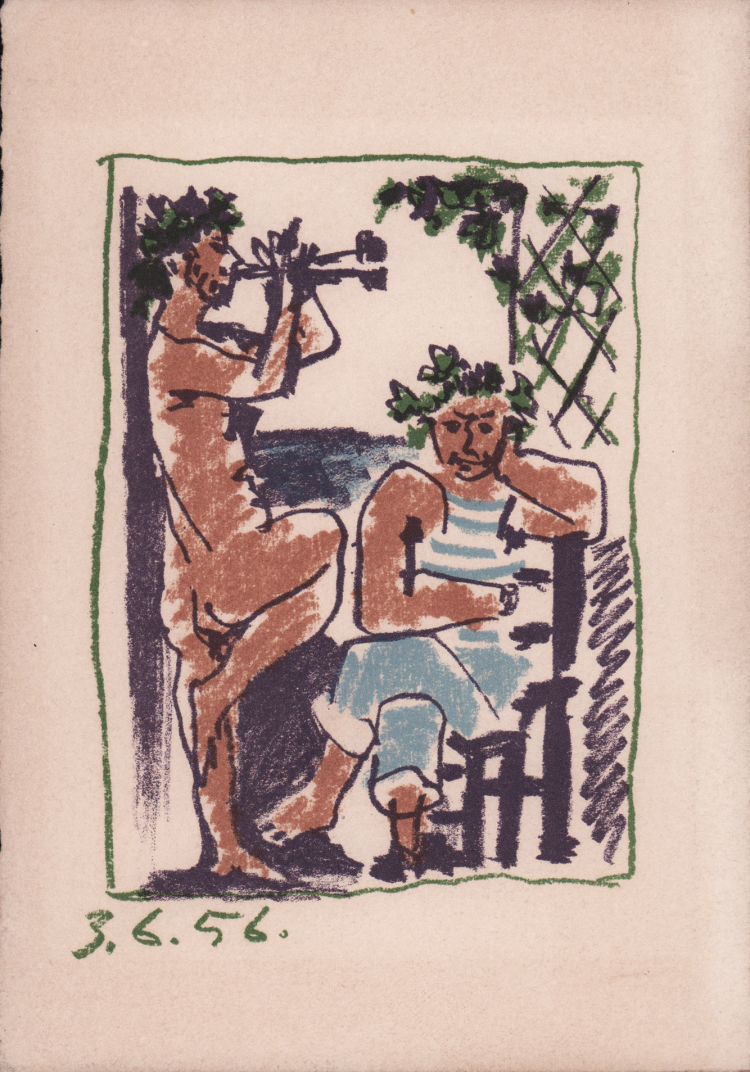

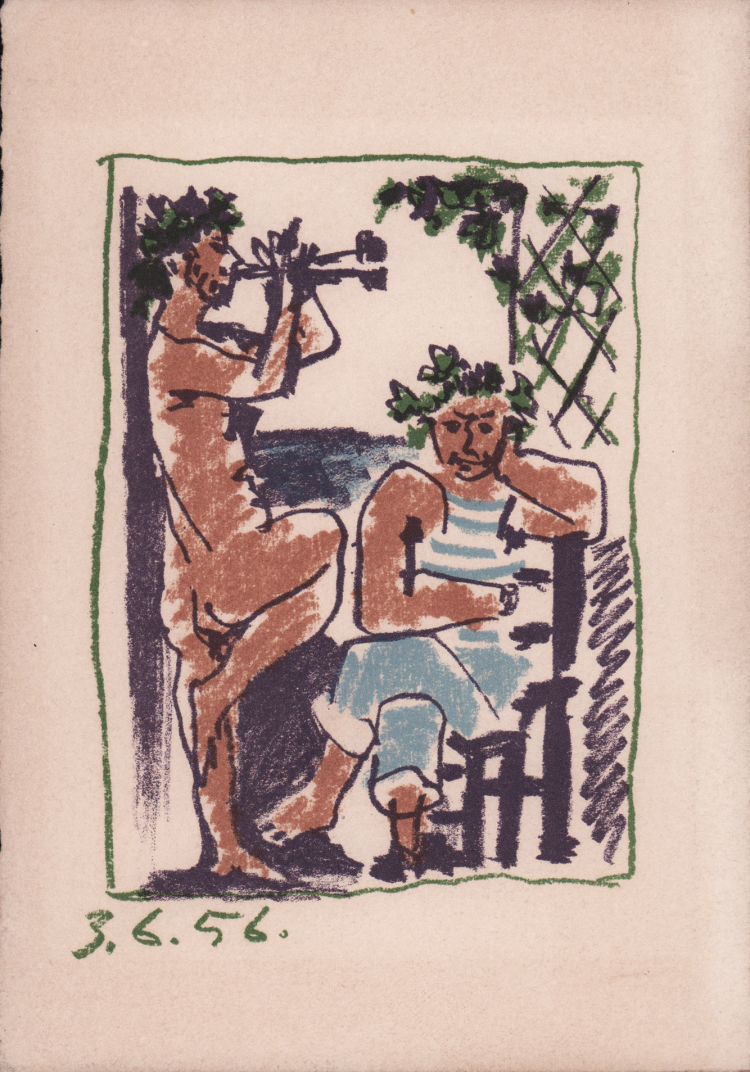

Color lithograph, June 3, 1956, made by the artist as a cover for the catalog of his exhibition at Galerie 65 in Cannes.

Edition and Printing: 1500 unnumbered copies, including 50 special numbered copies with an additional print of the lithograph signed by the artist. Cannes, July 1956.

Gallery 65 in Cannes opened in 1954 with a Picasso exhibition. Two years later, Gilberte Duclaud organized a second Picasso exhibition to cater to Picassian tourists, as she explains in the preface to the catalog. The exhibition included etchings, lithographs, and drawings from 1905 to 1956 and, as a special attraction, the portrait of Sylvette David, 1954 (Z. XVI, 306), the young girl with the ponytail who had temporarily fascinated Picasso as a model.

On June 3, 1956, Picasso made two lithographs of a man sitting in a sailor's shirt listening to a faun playing a flute, first in black and white (Mourlot 283), then in four-color (Mourlot 284); the last one constitutes the original in this exhibition catalog.

Exemplar in perfect condition.

Bibliografia

Bloch, G. (1984). Pablo Picasso, Tome I Catalogue de l’œuvre grave et lithographié 1904 – 1967, n. 800; Bloch, livres, 76; O'Brian, 1976; Mourlot 284.

|

Painter and sculptor (Malaga 1881 - Mougins, Alpes-Maritimes, 1973). Among the absolute protagonists of twentieth-century art, he represented a crucial junction between the nineteenth-century tradition and contemporary art. The son of José Ruiz, professor of drawing and curator of the Malaga museum, P. (from 1901 onwards he would sign with his mother's surname) began drawing at a very young age; when the family moved to Barcelona (1895), he took part in the intellectual life of the city, open to all avant-garde currents, worked frantically experimenting with various techniques, drawing scenes from life, portraits of friends, and posters for Hostels els

Quatre Gats, meeting place of young intellectuals. In October 1900 he went to Paris for the first time and is interested mainly in the art of Steinlen, Toulouse-Lautrec, Vuillard. In the following years P. returns to Paris and finally in 1904 he settled there (he will leave only for short periods). Between 1901 and 1904 his works, which propose again in the themes painful expressions of tragic human and social conditions, are characterized by a stylized and sharp drawing, by a blue monochrome intonation that harshly defines the volumes (blue period). From 1904 acrobats, street musicians, harlequins populate his canvases and his drawings, with notes of tender melancholy, while the blue is replaced by gray-pink tones (pink period). The Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906, New York, Metropolitan Museum) is a prelude in the simplification and solidity of the forms to the paintings more directly influenced by black art, of which P. feels acutely the charm. The Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907, New York, Museum of modern art) in its final version (after three versions and numerous studies) are at the center of an obsessive search for all the expressive possibilities of the human figure in the decomposition of volumes and in the schematic treatment of planes (the work, shown only to a few friends, will be reproduced in 1925 in La révolution surréaliste and presented in the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1937). From these premises and from a new and deeper knowledge of the work of Cézanne, Cubism was born. In a research that runs parallel to that of Braque, P. analyzes the volumetric elements of the images through their geometric decomposition into superimposed and juxtaposed planes, in a complex rhythm that leads to the overcoming of the traditional background-image setting. With the simultaneous presentation of the various faces of the image, going beyond the three-dimensional vision, realizes the fourth dimension on the plane (the forms become symbols of space and time) and simultaneously also develops his experiences in sculpture (Female head, bronze, 1909, Paris, Musée Picasso). From the analysis and dissection of the object that leads to the discovery of forms, constituting the formal elements of the composition (analytical cubism), Braque and P. arrive at the discovery of the process that, gradually, gives an objective meaning to compositions of purely pictorial elements (synthetic cubism); in this process great importance has the invention of papier collé and collage. In 1915 P. returns to objective representation, at first tracing, especially in the drawings, the path of the rigorous classicism of Ingres, then trying to achieve a new monumentality in a series of "colossal" figures, but soon refers, especially in still lifes, the decomposition of Cubist type. Against the classicist current, which dominates throughout Europe, P. insurges with a painting of Dancers (1925, London, Tate Gallery), in which the cubist decomposition is transformed into a real formal deflagration. Although P. did not explicitly adhere to Surrealism, the works of this period, in which the deformation often reaches a deliberate monstrosity, are considered Surrealist; only in the period called Bones (1928-29) is there a true Surrealist vision. But the formal instinct, plastic artist takes over the poetics of surrealism: with an important group of sculptures (1930-34, busts, female nudes, animals, metal constructions), born paintings of high expressive value, in which the deformation becomes moral apostrophe, a symbol of the inner deformations of modern man. During the Spanish Civil War P. lives with strong commitment to the drama of his country, for a short period is director of the Prado. The ruthless denunciation of the horrors of fascism and war, which imprints the violent etchings that illustrate the poem Sueño y mentira de Franco, reaches the highest tones of the drama in Guernica (now in the Museo Reina Sofia), expression of the most intense indignation after the German bombing of the town, resolved in a reduced chromatic range of whites and blacks: forced action in the space of a room, from the rubble, torn shreds of consciousness, emerges the bull, symbol of violence and brutality. The work, whose denunciation goes beyond the contingent episode that gave rise to it, exhibited in the Spanish pavilion at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1937, aroused deep emotion and approval. Symbols of horror are also the Minotaurs and the Tauromachie, as well as, during the Second World War, the monstrously deformed women and still lifes. After the war, it is a new period of détente; enrolled in the French Communist Party since 1944, P. participates in various peace congresses and executes the affiche with the dove for that of Paris in 1949. From 1947 he stayed in Vallauris, where he devoted himself mainly to ceramics, then in Cannes and from 1961 he settled in Mougins. While not abandoning the violent decomposition of form, P. knows how to bend it to express family affections, clear human feelings, with greater serenity in the classical myths and research in the ancient technique of ceramics the deep sense of the Mediterranean soul. His prodigious technique, his disruptive creative force, his ardent pathos come to expressions almost idyllic as in the great panel Peace, or high moral sense as in that War (both of 1952-54, Vallauris, Musée national Pablo Picasso). His last works include a series of variations on Velázquez's Las Meninas (1957, Barcelona, Picasso Museum) and on Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (1961) and a large mural for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris (1958).

|

|

Painter and sculptor (Malaga 1881 - Mougins, Alpes-Maritimes, 1973). Among the absolute protagonists of twentieth-century art, he represented a crucial junction between the nineteenth-century tradition and contemporary art. The son of José Ruiz, professor of drawing and curator of the Malaga museum, P. (from 1901 onwards he would sign with his mother's surname) began drawing at a very young age; when the family moved to Barcelona (1895), he took part in the intellectual life of the city, open to all avant-garde currents, worked frantically experimenting with various techniques, drawing scenes from life, portraits of friends, and posters for Hostels els

Quatre Gats, meeting place of young intellectuals. In October 1900 he went to Paris for the first time and is interested mainly in the art of Steinlen, Toulouse-Lautrec, Vuillard. In the following years P. returns to Paris and finally in 1904 he settled there (he will leave only for short periods). Between 1901 and 1904 his works, which propose again in the themes painful expressions of tragic human and social conditions, are characterized by a stylized and sharp drawing, by a blue monochrome intonation that harshly defines the volumes (blue period). From 1904 acrobats, street musicians, harlequins populate his canvases and his drawings, with notes of tender melancholy, while the blue is replaced by gray-pink tones (pink period). The Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906, New York, Metropolitan Museum) is a prelude in the simplification and solidity of the forms to the paintings more directly influenced by black art, of which P. feels acutely the charm. The Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907, New York, Museum of modern art) in its final version (after three versions and numerous studies) are at the center of an obsessive search for all the expressive possibilities of the human figure in the decomposition of volumes and in the schematic treatment of planes (the work, shown only to a few friends, will be reproduced in 1925 in La révolution surréaliste and presented in the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1937). From these premises and from a new and deeper knowledge of the work of Cézanne, Cubism was born. In a research that runs parallel to that of Braque, P. analyzes the volumetric elements of the images through their geometric decomposition into superimposed and juxtaposed planes, in a complex rhythm that leads to the overcoming of the traditional background-image setting. With the simultaneous presentation of the various faces of the image, going beyond the three-dimensional vision, realizes the fourth dimension on the plane (the forms become symbols of space and time) and simultaneously also develops his experiences in sculpture (Female head, bronze, 1909, Paris, Musée Picasso). From the analysis and dissection of the object that leads to the discovery of forms, constituting the formal elements of the composition (analytical cubism), Braque and P. arrive at the discovery of the process that, gradually, gives an objective meaning to compositions of purely pictorial elements (synthetic cubism); in this process great importance has the invention of papier collé and collage. In 1915 P. returns to objective representation, at first tracing, especially in the drawings, the path of the rigorous classicism of Ingres, then trying to achieve a new monumentality in a series of "colossal" figures, but soon refers, especially in still lifes, the decomposition of Cubist type. Against the classicist current, which dominates throughout Europe, P. insurges with a painting of Dancers (1925, London, Tate Gallery), in which the cubist decomposition is transformed into a real formal deflagration. Although P. did not explicitly adhere to Surrealism, the works of this period, in which the deformation often reaches a deliberate monstrosity, are considered Surrealist; only in the period called Bones (1928-29) is there a true Surrealist vision. But the formal instinct, plastic artist takes over the poetics of surrealism: with an important group of sculptures (1930-34, busts, female nudes, animals, metal constructions), born paintings of high expressive value, in which the deformation becomes moral apostrophe, a symbol of the inner deformations of modern man. During the Spanish Civil War P. lives with strong commitment to the drama of his country, for a short period is director of the Prado. The ruthless denunciation of the horrors of fascism and war, which imprints the violent etchings that illustrate the poem Sueño y mentira de Franco, reaches the highest tones of the drama in Guernica (now in the Museo Reina Sofia), expression of the most intense indignation after the German bombing of the town, resolved in a reduced chromatic range of whites and blacks: forced action in the space of a room, from the rubble, torn shreds of consciousness, emerges the bull, symbol of violence and brutality. The work, whose denunciation goes beyond the contingent episode that gave rise to it, exhibited in the Spanish pavilion at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1937, aroused deep emotion and approval. Symbols of horror are also the Minotaurs and the Tauromachie, as well as, during the Second World War, the monstrously deformed women and still lifes. After the war, it is a new period of détente; enrolled in the French Communist Party since 1944, P. participates in various peace congresses and executes the affiche with the dove for that of Paris in 1949. From 1947 he stayed in Vallauris, where he devoted himself mainly to ceramics, then in Cannes and from 1961 he settled in Mougins. While not abandoning the violent decomposition of form, P. knows how to bend it to express family affections, clear human feelings, with greater serenity in the classical myths and research in the ancient technique of ceramics the deep sense of the Mediterranean soul. His prodigious technique, his disruptive creative force, his ardent pathos come to expressions almost idyllic as in the great panel Peace, or high moral sense as in that War (both of 1952-54, Vallauris, Musée national Pablo Picasso). His last works include a series of variations on Velázquez's Las Meninas (1957, Barcelona, Picasso Museum) and on Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (1961) and a large mural for the UNESCO headquarters in Paris (1958).

|