| Reference: | S40221 |

| Author | Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) |

| Year: | 1582 |

| Zone: | SS. Cosma e Damiano |

| Measures: | 210 x 295 mm |

| Reference: | S40221 |

| Author | Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) |

| Year: | 1582 |

| Zone: | SS. Cosma e Damiano |

| Measures: | 210 x 295 mm |

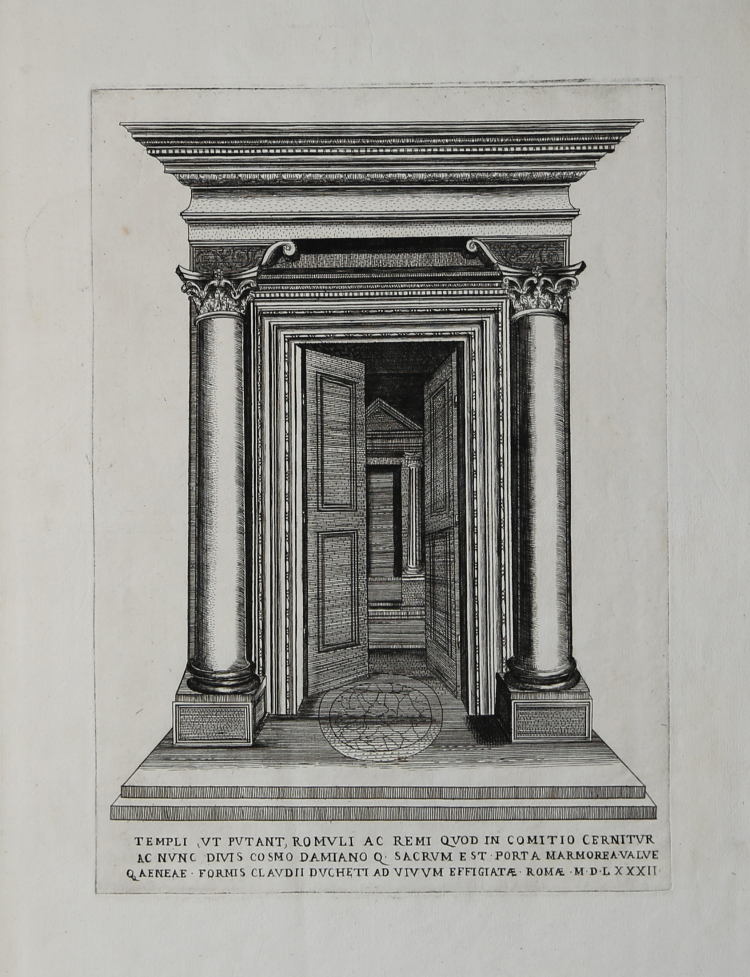

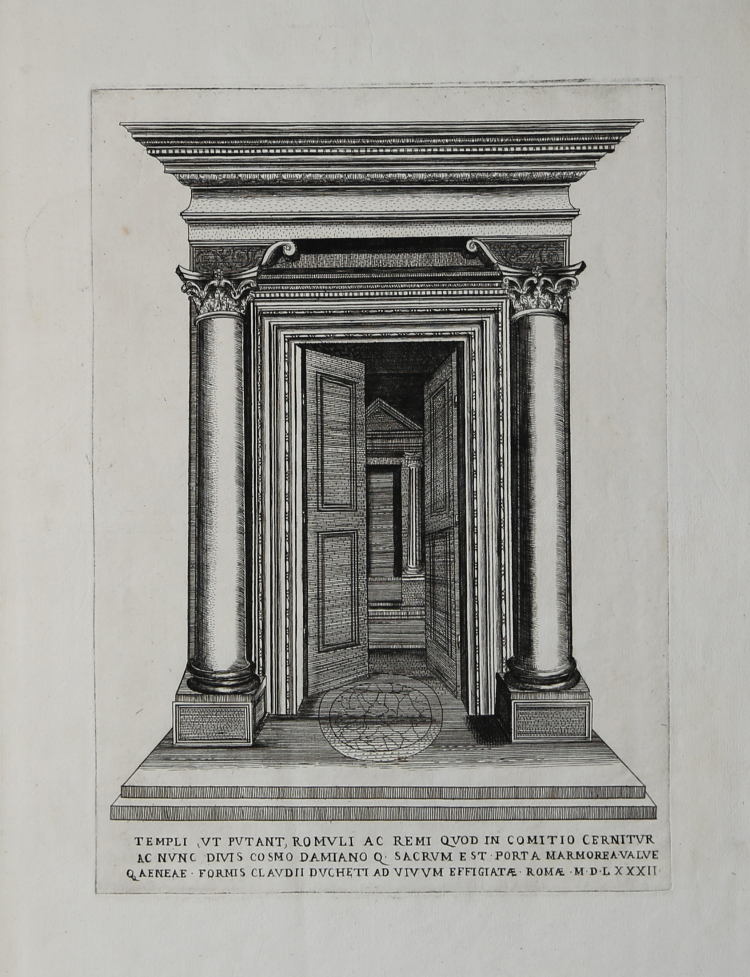

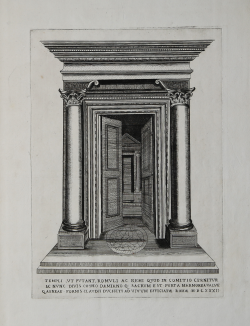

Engraving, signed and dated at the bottom center. Part of the "Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae".

Inscribed at the bottom center: "TEMPLI, VT PVTANT, ROMVLI AC REMI QVOD IN COMITIO CERNITVR AC NVNC DIVIS COSMO DAMIANO Q[VE] SACRVM EST - PORTA MARMOREA VALVE Q[VE] AENEAE - FORMIS CLAVDII DVCHETI AD VIVVM EFFIGIATÆ - ROMÆ - MDLXXXII ".

The so-called temple of Romulus has been attributed to the divinized son of Maxentius, but recent studies advance the hypothesis of a rededication at the time of Constantine to Jupiter Stator, to whom the first Romulus, founder of Rome, had vowed in the uncertain clash against the Sabines by Titus Tazio. In the sixth century AD the building was transformed into a church and dedicated to Saints Cosmas and Damian.

A first version of the work was printed by Lafréry in 1550 (see Rubach, n. 263, Alberti n. 39) in a sheet of paper that contained both the engraving of the Remains of the Temple of the Dioscuri and the Door of the so-called Temple of Romulus. The version presented here edited by Claude Duchet (1582), is part of the "Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae" edited by Lafreri's nephew, who made a new version of the subject - probably engraved by Ambrogio Brambilla - after having "lost" the original plate in the hereditary division following the disappearance of Lafrery (1577).

The work belongs to the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, the earliest iconography of ancient Rome.

The Speculum originated in the publishing activities of Antonio Salamanca and Antonio Lafreri (Lafrery). During their Roman publishing careers, the two editors-who worked together between 1553 and 1563-started the production of prints of architecture, statuary, and city views related to ancient and modern Rome. The prints could be purchased individually by tourists and collectors, but they were also purchased in larger groups that were often bound together in an album. In 1573, Lafreri commissioned a frontispiece for this purpose, where the title Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae appears for the first time. Upon Lafreri's death, two-thirds of the existing copperplates went to the Duchetti family (Claudio and Stefano), while another third was distributed among several publishers. Claudio Duchetti continued the publishing activity, implementing the Speculum plates with copies of those "lost" in the hereditary division, which he had engraved by the Milanese Amborgio Brambilla. Upon Claudio's death (1585) the plates were sold - after a brief period of publication by the heirs, particularly in the figure of Giacomo Gherardi - to Giovanni Orlandi, who in 1614 sold his printing house to the Flemish publisher Hendrick van Schoel. Stefano Duchetti, on the other hand, sold his own plates to the publisher Paolo Graziani, who partnered with Pietro de Nobili; the stock flowed into the De Rossi typography passing through the hands of publishers such as Marcello Clodio, Claudio Arbotti and Giovan Battista de Cavalleris. The remaining third of plates in the Lafreri division was divided and split among different publishers, some of them French: curious to see how some plates were reprinted in Paris by Francois Jollain in the mid-17th century. Different way had some plates printed by Antonio Salamanca in his early period; through his son Francesco, they goes to Nicolas van Aelst's. Other editors who contributed to the Speculum were the brothers Michele and Francesco Tramezzino (authors of numerous plates that flowed in part to the Lafreri printing house), Tommaso Barlacchi, and Mario Cartaro, who was the executor of Lafreri's will, and printed some derivative plates. All the best engravers of the time - such as Nicola Beatrizet (Beatricetto), Enea Vico, Etienne Duperac, Ambrogio Brambilla, and others - were called to Rome and employed for the intaglio of the works.

All these publishers-engravers and merchants-the proliferation of intaglio workshops and artisans helped to create the myth of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae, the oldest and most important iconography of Rome. The first scholar to attempt to systematically analyze the print production of 16th-century Roman printers was Christian Hülsen, with his Das Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae des Antonio Lafreri of 1921. In more recent times, very important have been the studies of Peter Parshall (2006) Alessia Alberti (2010), Birte Rubach and Clemente Marigliani (2016).

Magnificent proof, printed on contemporary paper with watermark "anvil and hammer in a circle with cross" (Woodward nn. 231-232), with margins, in excellent condition. Rare.

Bibliografia

cfr. B. Rubach, Ant. Lafreri Formis Romae (2016), n. 270; cfrr. A. Alberti, L’indice di Antonio Lafrery (2010), n. 39; Marigliani, Lo splendore di Roma nell’Arte incisoria del Cinquecento (2016), n. II.21; C. Hülsen, 1921, p. 144, 7, B; G. Milesi, 1989, p. 85; F. Coarelli, 2001, pp. 108-09.

Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) (Attivo a Roma nella seconda metà del XVI sec.))

|

Print dealer and publisher.Active in Venice 1565-1572 and Rome.He was the brother of Francesco Duchetti and a nephew of Antonio Lafrery, inheriting half his plates.

Died 5 December 1585.He was buried in San Luigi dei Francesi.By the terms of his will, his brother –in-law Giacomo Gherardi was to run the business until the majority of Claudio’s son, Claudio.

While Gherardi in charge, he was to inscribe the prints ‘haeredes Claudii Duchetti’.

He commissioned plates from among others Perret, Thomassin and Brambilla.

The name 'Lafreri-School' is a widely used, but rather inaccurate, term used to describe a loose grouping of cartographers, mapmakers, engravers and publishers working in the twin centres of Rome and Venice, from about 1544 to circa 1585. Earlier this century, George Beans, a prominent American collector of Italian maps and atlases, proposed the alternative name 'I.A.T.O.' to describe the composite collections assembled and sold by this school - 'Italian, Assembled-To-Order'. While more apposite, it has failed to catch on with modern cataloguers and collectors. For the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to the cartographers, engravers and publishers involved as "the school", although even this term implies a greater structure and organisation than can currently be established. The principal reference source on the work of the school is R.V. Tooley's Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century (1). In his study, published in 1939, Tooley listed some 614 maps and plates (with variant states counted separately). Some were described from personal examination, others noted from secondary sources and listings. While now much out-dated, as more recent regional carto-bibliographies have effectively superceded particular sections, and new collections have come to light, it remains the only overview of the output of the school. The principal cartographer of the school was Giacomo Gastaldi (fl. 1542-1565), a Piedmontese who worked in Venice, becoming Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic. Karrow described him as "one of the most important cartographers of the sixteenth century. He was certainly the greatest Italian mapmaker of his age..." (2). While his achievement is obvious, it is hard to quantify. A large number of maps were published throughout this period with the geography credited to Gastaldi, but it is often difficult to know what role Gastaldi played in their creation. As a practice, he did not sign himself as publisher, although his name may be found in the title, dedication, or text to the reader. Frequently where there is no imprint one may assume that Gastaldi was the publisher. A further clue may be that many of the maps attributable to Gastaldi as publisher seem to have been engraved by Fabius Licinius. In other cases, where publication is credited to another, it is not always certain whether Gastaldi was commissioned by the publisher to compile the map, whether another less-enterprising publisher merely copied his work and attribution, or simply added Gastaldi's name in the title to add authority to the delineation. His name clearly commanded the same sort of respect that the Sanson name had in the last years of the seventeenth century, and as Guillaume de l'Isle's had in the first half of the eighteenth century. Paolo Forlani was a cartographer and engraver who worked in Venice between 1560 and circa 1571. The majority of his output was published under the imprint of other publishers, such as Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Ferrando Bertelli and Bolognini Zaltieri. In a pioneering study, David Woodward (4), by identifying Forlani's engraving style through various stages of development, has attributed a large number of previously unidentified maps to his hand, and provided a clearer picture of some of the publishing arrangements of the period. In the early 1560s Giovanni Francesco Camocio published a number of maps that were drawn by Forlani, including maps of the World, North Atlantic, Africa, France, Switzerland, and provinces of the Low Countries, to note but a few. Circa 1570, Camocio published an Isolario, or collection of maps of islands, principally from the Mediterranean, but including the British Isles and Iceland. Camocio's earliest issues lacked a title-page, and tended to be a relatively random selection from the available stock. Later he added a title Isole Famose Porti, Fortezze E Terre Maritime. After his death, which is assumed to have been in 1573, the plates were reprinted, with a title-page bearing the Bertelli family address 'alla Libraria del Segno di S. Marco', possibly by Donato Bertelli, whose imprint is found on a later state of Camocio's world map of 1560. The largest grouping was the Bertelli family. The most active was Ferrando Bertelli, who flourished in the 1560's and 1570's, but maps from the last quarter of the seventeenth century are known with the imprints of Andrea, Donato, Lucca, Nicolo and Pietro. Again, a number of maps published by Ferrando were drawn or engraved by Forlani.

Antonio Salamanca (1500 – 1562) settled in Rome his chalcographical business; his activity was then carried on and enlarged by his scholar Antonio Lafrery (1512 – 1577), and then by his grand son Claudio Duchet (Duchetti), Giovanni Orlandi, Henrik van Schoel, and finally by De Rossi. In Venice, the most important centre of map production, he was initiated into engraving by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore and Matteo Pagano, who had worked with Giacomo Gastaldi, the most important European cartographer of the XVI century. Other important exponents of the Venetian chalcography were Fabio Licinio, Fernando Bertelli, Giovanni Francesco Camocio and above all of them Paolo Forlani. Although he’s better known as publisher of Roman archeology, Antoine de Lafrery, born in France, has been the publisher thathas given the biggest impulse to Roman chalcography, becoming in a few years an expert seller as well. For that reason, even though he’s not the one that has published most maps in his time, all the chalcographic works printed in Rome and Venice during the XVI century are nowadays defined as “charts of lafrerian school”. This definition was given by Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, one of the fathers of the history of cartography, who also introduced the definition of Lafrery Atlas, talking about charts printed in Rome and published by Lafrery, in which we find a sort of title page with the title Tavole moderne de geografia secondo l’ordine di Tolomeo. Lafrery’s school produced a huge amount of maps, usually selling them as separate charts and somehow and then edited in a bigger volume. Since the charts had all different measures, the artists needed to trim them with copper to get them to the same size, adding at the end estra pieces of paper, if necessary.

|

Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) (Attivo a Roma nella seconda metà del XVI sec.))

|

Print dealer and publisher.Active in Venice 1565-1572 and Rome.He was the brother of Francesco Duchetti and a nephew of Antonio Lafrery, inheriting half his plates.

Died 5 December 1585.He was buried in San Luigi dei Francesi.By the terms of his will, his brother –in-law Giacomo Gherardi was to run the business until the majority of Claudio’s son, Claudio.

While Gherardi in charge, he was to inscribe the prints ‘haeredes Claudii Duchetti’.

He commissioned plates from among others Perret, Thomassin and Brambilla.

The name 'Lafreri-School' is a widely used, but rather inaccurate, term used to describe a loose grouping of cartographers, mapmakers, engravers and publishers working in the twin centres of Rome and Venice, from about 1544 to circa 1585. Earlier this century, George Beans, a prominent American collector of Italian maps and atlases, proposed the alternative name 'I.A.T.O.' to describe the composite collections assembled and sold by this school - 'Italian, Assembled-To-Order'. While more apposite, it has failed to catch on with modern cataloguers and collectors. For the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to the cartographers, engravers and publishers involved as "the school", although even this term implies a greater structure and organisation than can currently be established. The principal reference source on the work of the school is R.V. Tooley's Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century (1). In his study, published in 1939, Tooley listed some 614 maps and plates (with variant states counted separately). Some were described from personal examination, others noted from secondary sources and listings. While now much out-dated, as more recent regional carto-bibliographies have effectively superceded particular sections, and new collections have come to light, it remains the only overview of the output of the school. The principal cartographer of the school was Giacomo Gastaldi (fl. 1542-1565), a Piedmontese who worked in Venice, becoming Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic. Karrow described him as "one of the most important cartographers of the sixteenth century. He was certainly the greatest Italian mapmaker of his age..." (2). While his achievement is obvious, it is hard to quantify. A large number of maps were published throughout this period with the geography credited to Gastaldi, but it is often difficult to know what role Gastaldi played in their creation. As a practice, he did not sign himself as publisher, although his name may be found in the title, dedication, or text to the reader. Frequently where there is no imprint one may assume that Gastaldi was the publisher. A further clue may be that many of the maps attributable to Gastaldi as publisher seem to have been engraved by Fabius Licinius. In other cases, where publication is credited to another, it is not always certain whether Gastaldi was commissioned by the publisher to compile the map, whether another less-enterprising publisher merely copied his work and attribution, or simply added Gastaldi's name in the title to add authority to the delineation. His name clearly commanded the same sort of respect that the Sanson name had in the last years of the seventeenth century, and as Guillaume de l'Isle's had in the first half of the eighteenth century. Paolo Forlani was a cartographer and engraver who worked in Venice between 1560 and circa 1571. The majority of his output was published under the imprint of other publishers, such as Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Ferrando Bertelli and Bolognini Zaltieri. In a pioneering study, David Woodward (4), by identifying Forlani's engraving style through various stages of development, has attributed a large number of previously unidentified maps to his hand, and provided a clearer picture of some of the publishing arrangements of the period. In the early 1560s Giovanni Francesco Camocio published a number of maps that were drawn by Forlani, including maps of the World, North Atlantic, Africa, France, Switzerland, and provinces of the Low Countries, to note but a few. Circa 1570, Camocio published an Isolario, or collection of maps of islands, principally from the Mediterranean, but including the British Isles and Iceland. Camocio's earliest issues lacked a title-page, and tended to be a relatively random selection from the available stock. Later he added a title Isole Famose Porti, Fortezze E Terre Maritime. After his death, which is assumed to have been in 1573, the plates were reprinted, with a title-page bearing the Bertelli family address 'alla Libraria del Segno di S. Marco', possibly by Donato Bertelli, whose imprint is found on a later state of Camocio's world map of 1560. The largest grouping was the Bertelli family. The most active was Ferrando Bertelli, who flourished in the 1560's and 1570's, but maps from the last quarter of the seventeenth century are known with the imprints of Andrea, Donato, Lucca, Nicolo and Pietro. Again, a number of maps published by Ferrando were drawn or engraved by Forlani.

Antonio Salamanca (1500 – 1562) settled in Rome his chalcographical business; his activity was then carried on and enlarged by his scholar Antonio Lafrery (1512 – 1577), and then by his grand son Claudio Duchet (Duchetti), Giovanni Orlandi, Henrik van Schoel, and finally by De Rossi. In Venice, the most important centre of map production, he was initiated into engraving by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore and Matteo Pagano, who had worked with Giacomo Gastaldi, the most important European cartographer of the XVI century. Other important exponents of the Venetian chalcography were Fabio Licinio, Fernando Bertelli, Giovanni Francesco Camocio and above all of them Paolo Forlani. Although he’s better known as publisher of Roman archeology, Antoine de Lafrery, born in France, has been the publisher thathas given the biggest impulse to Roman chalcography, becoming in a few years an expert seller as well. For that reason, even though he’s not the one that has published most maps in his time, all the chalcographic works printed in Rome and Venice during the XVI century are nowadays defined as “charts of lafrerian school”. This definition was given by Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, one of the fathers of the history of cartography, who also introduced the definition of Lafrery Atlas, talking about charts printed in Rome and published by Lafrery, in which we find a sort of title page with the title Tavole moderne de geografia secondo l’ordine di Tolomeo. Lafrery’s school produced a huge amount of maps, usually selling them as separate charts and somehow and then edited in a bigger volume. Since the charts had all different measures, the artists needed to trim them with copper to get them to the same size, adding at the end estra pieces of paper, if necessary.

|