| Reference: | S47045 |

| Author | Camillo PROCACCINI |

| Year: | 1587 ca. |

| Measures: | 340 x 565 mm |

| Reference: | S47045 |

| Author | Camillo PROCACCINI |

| Year: | 1587 ca. |

| Measures: | 340 x 565 mm |

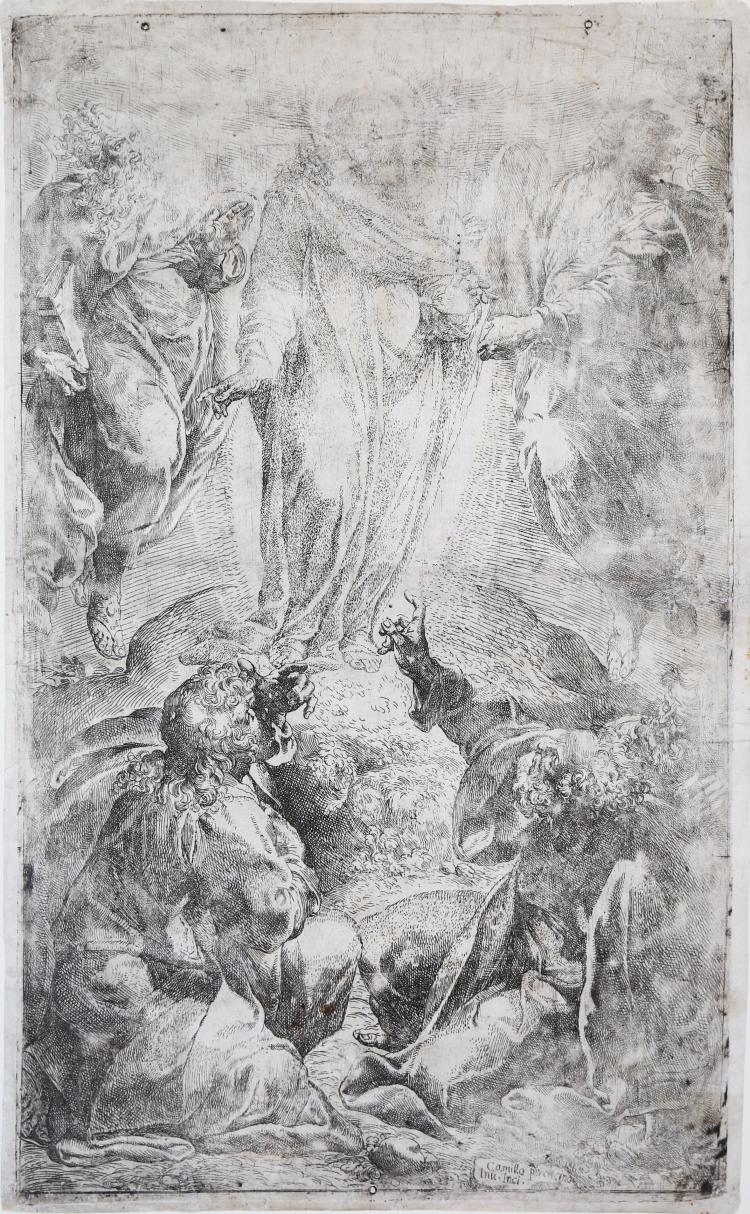

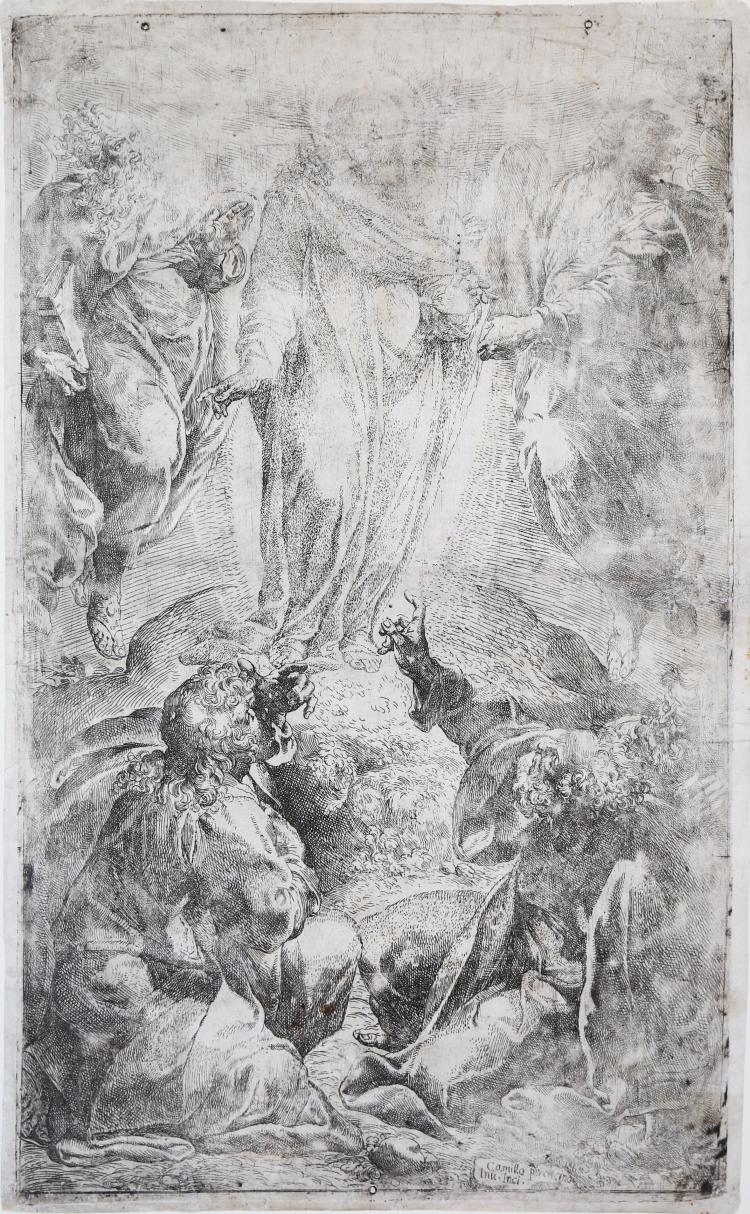

The Transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor, with Moses and Elijah, and three disciples cowering below.

Etching, circa 1587-1590, signed at lower center Camillo Percacino Inv. Inci.

Example of the first state of two, before the reworking on the face of Christ.

A beautiful example, with the usual bite defects that characterize all copies of this famous engraving, printed on contemporary laid paper, traces of glue and stains visible on the reverse, where there is also a central fold with restored printing creases. Overall, in good condition.

“This etched Transfiguration repeated the composition of a painting that Procaccini made early in his Milanese career, between 1587 and 1590, for the church of San Fedele. He repeated the subject for the organ shutters of the Milan cathedral between 1592 and 1595, but with changes in pose and the addition of a fourth Apostle kneeling on the ground. The print shown here was made at the beginning of the establishment of the artist's reputation in Milan and may be regarded as an advertisement of his skills. Although a smaller, contemporaneous print, The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, suggests a private devotional image, The Transfiguration, which is exceptionally large for an etching of its time, promoted Procaccini's abilities as the designer and executor of large altarpieces. Both prints were signed "Percacino," the Bolognese spelling of his name.

The Transfiguration of Christ is viewed as a prefiguration of the Resurrection. Three of Christ's followers, Peter, James, and John, accompanied him to a remote hill, where they saw him "transfigured before them; and his face did shine as the sun, and his garments became white as the light" (Matthew 17:2). The disciples saw and heard Elijah and Moses talking with Jesus (the moment depicted in Procaccini's print). Then, hearing the voice of God, the disciples fell on their faces. When they looked up, the vision had vanished, and Jesus was him-self again.

Procaccini's monumental figures and long, tubular folds of drapery resemble those of Bartolommeo Passarotti, whose broadly executed etchings, with their use of broken lines to create auras of light, must certainly have had an impact on the younger Bolognese artist. Procaccini's etching is more advanced in style, more directly appealing to the viewer, and more atmospheric than Passarotti's work and indeed than most of Procaccini's own paintings and drawings. The artist drew broadly and etched lines deeply except where he inventively depicted the body of Christ using strokes, employing neither continuous outlines nor short, stippled cross-hatching. This startling paleness, appropriate to the narrative, is both a spiritual strength and a physical weakness of the plate. Only in heavily inked impressions, are both eyes of Christ visible; in more cleanly wiped impressions, only the right eye can be seen. At some later date, Christ's head was defined more explicitly, in an unsympathetic fashion.

From the outset, the plate appears to have been seriously scratched. Patches of fine, vertical lines run at random along the surface of the plate, especially visible above and on the figure of Moses at the upper right. Underbitten, pale areas on the draperies, notably along the right side, are consistently visible in all impressions, but the mottled effect is reduced in richly inked impressions.

The three holes drilled through the upper and lower borderlines of the plate were probably made in order to fasten it to a rigid surface and prevent its curling from the pressure of the printing-press roller.

Most of Procaccini's other etchings followed this pattern of breadth of line, strong draftsmanship, and technical problems, including foul biting and poorly bitten areas that did not hold ink well. The best impressions are generously inked. Despite the technical problems of The Transfiguration, Procaccini's bold conception and broad execution make this etching his most dramatically effective production and one of the most audacious and powerful etchings of the sixteenth century” (cf. Sue Welsh Reed, Italian Etchers of the Reinassance & Barocque, pp. 74-76).

“The three holes (two at the top and one at the bottom) are interpreted by Reed as having been used to attach the plate to a rigid surface in order to prevent it curling when it went though the press. However the holes were apparently present before the border lines were engraved. One possible explanation is that the holes were to secure the plate during the processes of smoothing and polishing its surface prior to the laying of the ground. The need to secure it firmly when embarking on this process was stressed by Browne: 'First fasten your plate with some small nails to a place that is as high as your middle, then use the plain to shave all the roughness off from it and make it very even in all places alike…' (Alexander Browne, 'Ars Pictoria' 1669, p.108).

The surface of the plate was left covered with scratches. It is in the end impossible to say whether this was done deliberately, or whether it was the result of an inadequate burnishing; however the heavy scratches towards the top, especially at the right do seem rather disfiguring. Perhaps the plate was acquired in a rough state and prepared by Procaccini himself or by some relatively inexperienced assistant.

Malvasia wrote of it: '..tagliata all’acqua forte…con tanta bizzarria e ghiotezza' (Malvasia, 1841, I, p.222). Whatever imperfections there may have been on the surface of the plate, the expressive vitality of the resulting image is remarkable. It represents the Transfiguration, when Christ was seen accompanied by Moses and Elijah, his face shining like the sun and his garments white with light. The etching with its subtle gradations of tone, almost dissolves Christ in intense mystical light, his face barely seen. Procaccini was resourceful in finding means to achieve his effects. In the figure of Christ he used stippling without even contour lines.

Neilson dates the plate to between 1587 and 1590, during Procaccini's first years in Milan (Neilson, 1976, pp.699-701). The close relationship with his altarpiece of the Transfiguration, once in S. Fedele in Milan, which he is known to have painted by 1590, reinforces that hypothesis. In the two dated prints of 1593, his name is spelled Procacino and he is explicitly identified as Bolognese (Bartsch XVIII.19.2 and 21.5). In the present case, the use of the Bolognese spelling of his name - Percacino - and the lack of any indication of his place of origin, could be used to argue that it was done with the idea of having it printed and distributed in Bologna” (cf. Michael Bury, The Print in Italy 1550-1620).

Born in Bologna and educated as a painter by his father Ercole (1520-1595), Camillo Procaccini entered the guild of painters there in 1971. Around 1980 he began to execute independent commissions for religious pictures. In the mid-1580s he traveled to Parma to study Correggio's work and saw paintings being executed by Agostino and Annibale Carracci. He also worked in Reggio nell'Emilia between 1585 and 1587. By 1587 Procaccini's family, including his much younger brother Giulio Cesare, had moved to Milan, where painters were needed to decorate many new and renovated churches. There Procaccini made his reputation and continued to work virtually without cessation until his death in 1629.

Although the clarity of his narrative was responsive to the requirements of the Counter-Reformation, Procaccini's smooth-surfaced paintings were closer to the Mannerist style of the generation born between 1520 and 1530, including Bartolommeo Passarotti; he was virtually unaffected by the more direct, emotional, Baroque style forged in Milan by his brother Giulio Cesare and others. He made finished drawings, many in red chalk, including revivals of Leonardo da Vinci's grotesque heads, for a private collectors' market. He made six etchings between 1987 and 1600, two dated 1593. Ambitious and bold, his prints exhibit technical difficulties that do not detract from their impact.

Bibliografia

Bartsch vol. 18, p. 20, n. 4 I/II; Welsh & Reed, Italian Etchers of the Reinassance & Barocque, pp. 74-76. n. 34; Michael Bury, The Print in Italy 1550-1620, BM 2001, cat.19.

Camillo PROCACCINI (Bologna 1551 circa – Milano 1629)

|

Painter, printmaker and draughtsman, son of Ercole Procaccini. He was first mentioned in 1571 as a student in the Bolognese painters’ guild when his father, Ercole, was its head. This, and the stylistic maturity of his earliest surviving documented works, the frescoes (1585–7) in St Prospero, Reggio Emilia, suggest his date of birth. Trained by his father, he went to Rome c. 1580 with Conte Pirro Visconti, an important Milanese collector. His studies in Rome, particularly of the art of Taddeo Zuccaro, clearly affected his work after his return to Bologna. In 1582 he decorated the side walls of the apse of St Clemente, Collegio di Spagna, Bologna, and these frescoes (partially photographed before their destruction in 1914) seem to have been an energetic reflection of the exaggerated forms and contrasts of scale typical of mid-16th-century central Italian painting

|

Camillo PROCACCINI (Bologna 1551 circa – Milano 1629)

|

Painter, printmaker and draughtsman, son of Ercole Procaccini. He was first mentioned in 1571 as a student in the Bolognese painters’ guild when his father, Ercole, was its head. This, and the stylistic maturity of his earliest surviving documented works, the frescoes (1585–7) in St Prospero, Reggio Emilia, suggest his date of birth. Trained by his father, he went to Rome c. 1580 with Conte Pirro Visconti, an important Milanese collector. His studies in Rome, particularly of the art of Taddeo Zuccaro, clearly affected his work after his return to Bologna. In 1582 he decorated the side walls of the apse of St Clemente, Collegio di Spagna, Bologna, and these frescoes (partially photographed before their destruction in 1914) seem to have been an energetic reflection of the exaggerated forms and contrasts of scale typical of mid-16th-century central Italian painting

|