Jupiter Temple Base

Monogrammista G.A. (Maestro del Trabocchetto)

Code:

S45067

Measures:

215 x 335 mm

Year:

1530 ca.

Printed:

Rome

Reconstruction of Agrippa's Palace

Monogrammista G.A. (Maestro del Trabocchetto)

Code:

S45062

Measures:

185 x 140 mm

Year:

1530 ca.

Reconstruction of Claudius' Palace

Monogrammista G.A. (Maestro del Trabocchetto)

Code:

S45061

Measures:

135 x 190 mm

Year:

1530 ca.

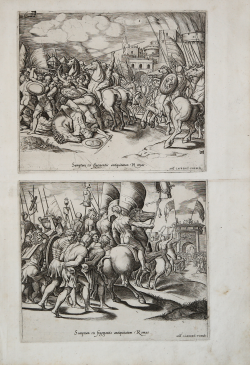

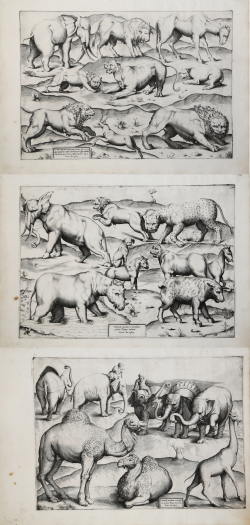

Victory of Scipio against Siface & Triumph of Scipio

Maestro B nel Dado

Code:

S45041

Measures:

255 x 440 mm

Year:

1535 ca.

Sheet with four column bases

Agostino de Musi detto VENEZIANO

Code:

S45066

Measures:

415 x 270 mm

Year:

1536

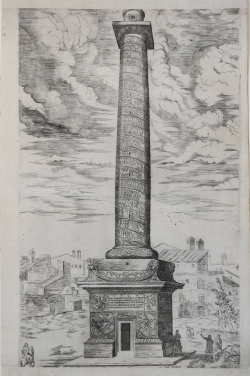

The Emperor Trajan offers a sacrifice

Leon DAVENT detto "Maestro L.D."

Code:

S10934

Measures:

472 x 267 mm

Year:

1545 ca.

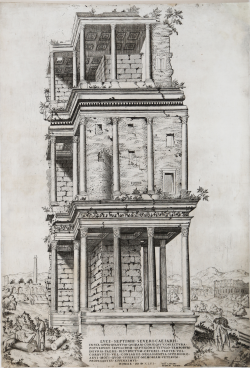

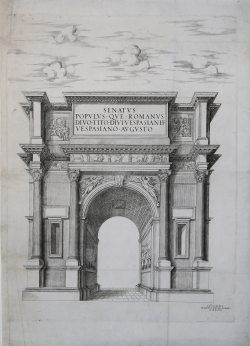

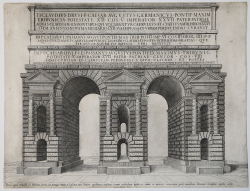

IMP. CAES. LVCIO. SEPTIMIO. M. FIL. SEVERO...

Antonio LAFRERI

Code:

S45012

Measures:

400 x 440 mm

Year:

1547

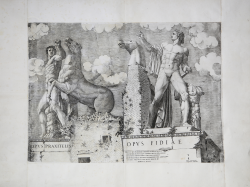

The Roma Cesi or Allegory of Rome

Nicolas Beatrizet detto BEATRICETTO

Code:

S20850

Measures:

380 x 445 mm

Year:

1549

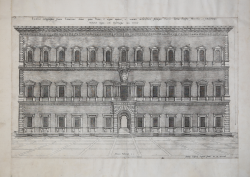

Exterior orthographia frontis Farnesianae domus…

Nicolas Beatrizet detto BEATRICETTO

Code:

S402420

Measures:

535 x 335 mm

Year:

1549

Printed:

Rome

Veteris aquae Claudiæ ex Tiburtino forma

Antonio LAFRERI

Code:

S40217

Measures:

480 x 365 mm

Year:

1549

The Roma Cesi or Allegory of Rome

Nicolas Beatrizet detto BEATRICETTO

Code:

S45046

Measures:

390 x 490 mm

Year:

1549

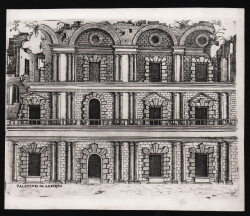

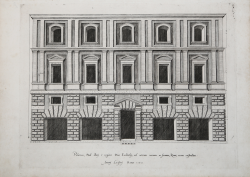

Maccarani States Building (Cenci Palace)

Antonio LAFRERI

Code:

S45059

Measures:

420 x 325 mm

Year:

1549