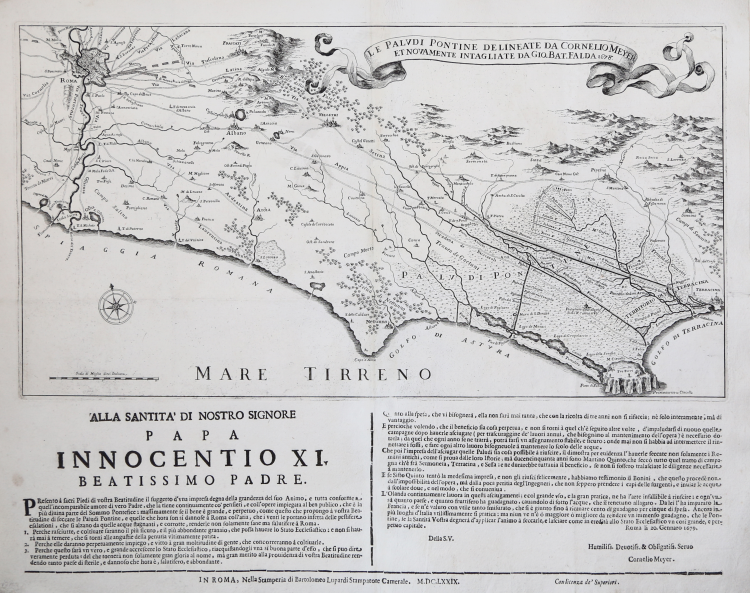

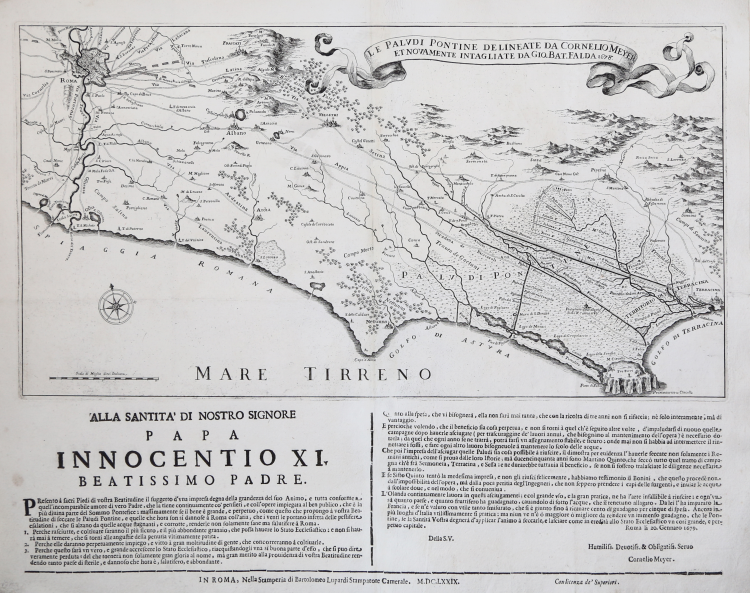

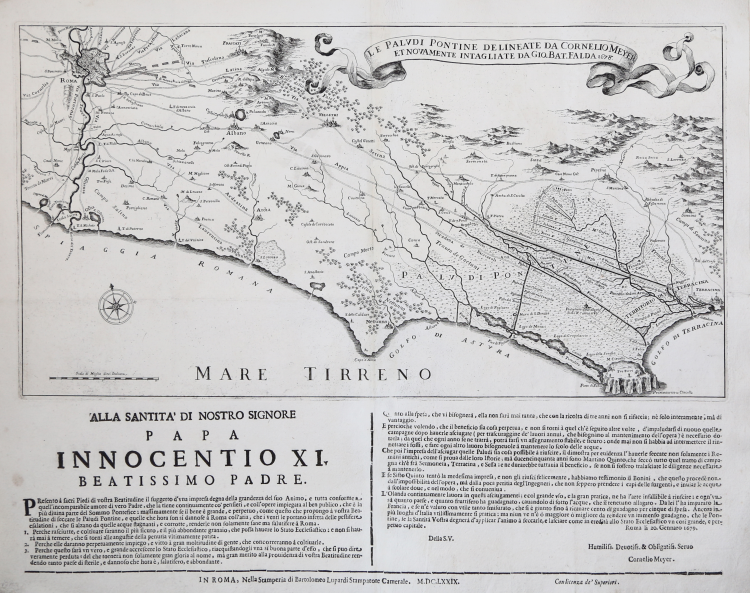

| Reference: | CO-419 |

| Author | Cornelis Janszoon Meijer |

| Year: | 1678 |

| Zone: | Paludi Pontine |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 490 x 260 mm |

| Reference: | CO-419 |

| Author | Cornelis Janszoon Meijer |

| Year: | 1678 |

| Zone: | Paludi Pontine |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 490 x 260 mm |

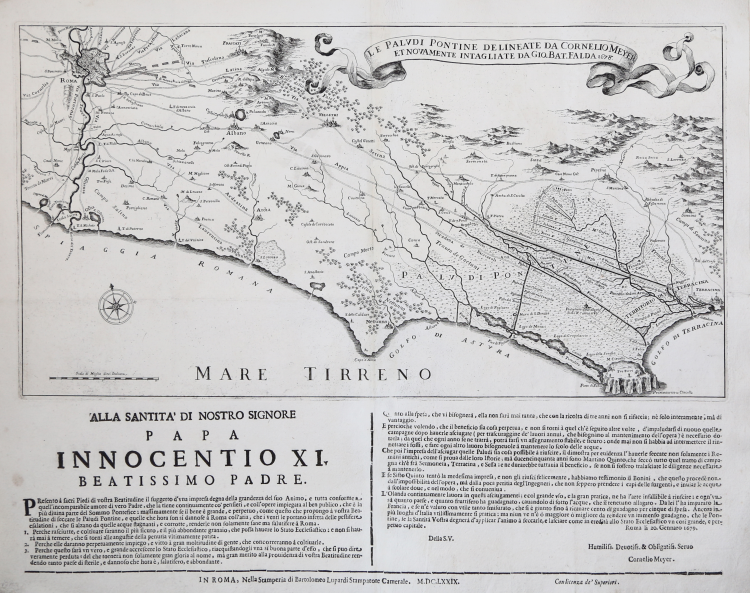

RARISSIMO ESEMPLARE DI PRESENTAZIONE A PAPA INNOCENZO XI

Si tratta di una prima stesura, di incredibile rarità, della carta delle Paludi Pontine di Cornelis Meyer, incisa da Giovan Battista Falda nel 1678 e presentata al Papa il 20 gennaio 1679 (come da data nella dedica in basso). Viene stampata, come singolo foglio, IN ROMA, Nella Stamperia di Bartolomeo Lupardi Stampatore Camerale. M.DC.LXXIX. Con licenza de’ Superiori (imprint in basso nel foglio, che segue la dedica impressa con caratteri tipografici.

Dal punto di vista cartografico, notiamo la straordinaria importanza dell’assenza di tre canali di collegamento che furono successivamente inseriti nella versione definitiva della carta inserita nell’Arte di restituire a Roma la tralasciata navigazione del suo Tevere, del Meyer, stampato a Roma nel 1683. Si tratta del canale che unisce il fiume Albano al Lanuvio e questi, attraverso un ulteriore canale passante nella Tenuta Caetani, al Fiume Sisto. Altro canale assente in questa prima edizione della carta è quello che devia il Fiume Ninfa a sud di Nettuno.

Nel 1677, per ordine di papa Innocenzo XI, Meyer e l'abate Innocenzo Boschi perlustrarono le paludi pontine. Boschi era stato incaricato dalla Camera apostolica, Meyer voleva visionare le paludi in vista della bonifica che si era offerto di fare.

“I tentativi di bonifica del Seicento si chiudono con la richiesta di Cornelio Meyer a Papa Innocenzo XI (1676-1689) di visitare le paludi per programmare un intervento di prosciugamento. Due anni dopo la visita, nel 1678, l’olandese pubblicò una carta incisa in rame rappresentante i lavori idraulici progettati e in parte realizzati durante il pontificato di Innocenzo XI. Meyer e l’abate Innocenzo Boschi, incaricato dalla Camera Apostolica di perlustrare la palude, erano concordi nel riprendere le bonifiche di Sisto V, individuando nella zona dell’Eufente-Portatore un labirinto di acque nel quale era necessario intervenire.

Cornelius Meyer (1640-1700). Architetto, ingegnere, astronomo fu personalità di spicco nell'Europa del suo tempo e lavorò a numerosi progetti idrici, fra cui la sistemazione del corso del Tevere. Poligrafo dai multiformi e differenti interessi scrisse sui più disparati soggetti: accanto a dissertazioni ed ingegnose soluzioni ingegneristiche si trovano saggi sulle eclissi, ed immagini del drago le cui ossa l'Autore aveva recuperato nelle paludi pontine ed esposto a casa. Meyer, conosciuto già alla curia romana per aver ottenuto un incarico per un progetto sulla navigabilità del Tevere pubblicò i suoi studi nell’opera L’arte di restituire a Roma la tralasciata navigazione del suo Tevere, in Roma nella Stamperia della Reverenda Camera Apostolica, 1683, con un capitolo intitolato Del modo di seccare le Paludi Pontine.

I problemi riscontrati erano gli stessi che si riproposero nelle bonifiche successive, ossia: la mancanza di opere di manutenzione che servissero a non rendere vani gli sforzi precedenti; l’inadeguatezza degli argini, in alcuni casi completamente divelti; la presenza massiccia e invasiva delle peschiere che con “passonate” e acconci ostruivano le acque, alteravano il corso dei fiumi e innalzavano il letto favorendo le esondazioni nelle pianure circostanti. A piena ragione, Boschi accusava la Congregazione delle paludi nella gestione diretta delle peschiere venendo meno a quell’azione di controllo per la quale l’organo era stato istituito. Tra i primi interventi quindi si proponeva proprio lo smantellamento delle costruzioni per la pesca, operazione primaria anche durante le bonifiche di Pio VI. Meyer individuò anche nella mancanza della pendenza una delle cause al ristagno delle acque che non riuscivano a trovare uno sbocco al mare per l’eccessiva lentezza del loro scorrimento; problema che sarebbe stato superato allargando e scavando alvei più profondi per aumentare la portata e la velocità.

Nonostante i pareri tecnici prospettassero una positiva riuscita della bonifica, le trattative furono lente perché la Congregazione chiese il parere delle comunità pontine. Sezze, che aveva una vocazione più agricola rispetto alle altre, accolse positivamente la proposta di Meyer, perché le tenute da cui la comunità ricavava la maggior parte delle sue entrate erano costantemente minacciate dagli allagamenti. I setini si raccomandarono che nel circondario non rientrassero però i beni comuni costituiti da tenute, selve e pascoli. Contrari erano i privati che in quei terreni paludosi avevano gli allevamenti, ma soprattutto Terracina e in particolare il vescovo della città che beneficiava degli affitti delle peschiere di Soace, Stronzola, Canzo e Mortola. I terracinesi si lamentavano perché sostenevano che le bonifiche passate avevano rappresentato il pretesto per sottrarre alla comunità le sue terre, accrescendo per giunta il disordine idrico.

Nel 1699 i terreni paludosi passarono a Meyer che nominò il Duca Odescalchi di Bracciano come finanziatore dell’opera. Nel 1701, Massimo de Marchis commissario deputato per delineare il circondario di bonifica, visitò le paludi delimitando un’area molto simile a quella indicata a fine Cinquecento da Ascanio Fenizi. Le proteste di Terracina non si fecero attendere e riguardavano principalmente l’inclusione nel circondario della Selva, di inestimabile valore per la comunità. Odescalchi rispose che non si trattava di una selva bensì di un vero e proprio pantano che, una volta bonificato e messo a coltura, avrebbe reso in futuro molto di più. A Cornelis Meyer succedette il figlio Ottone che iniziò i lavori di spurgo del Ninfa e la costruzione di argini presso Acquapuzza. Le pressioni e le molestie delle comunità nei confronti di Meyer e di Odesclachi si fecero sempre più forti e causarono un rallentamento dei lavori. I bonificatori vennero accusati di commettere abusi sui beni comuni e di non versare gli indennizzi dovuti ai proprietari dei terreni espropriati. A nulla servì l’intervento di Clemente XI (1700-1721) che inviò alcuni cardinali (tra cui Spada nel 1704) per dirimere le controversie. Odescalchi si ritirò dall’impresa, che finora gli era costata 30.000 scudi, lasciando che gli venisse revocata la concessione di durata quarantennale”.

Magnifico esemplare di questa rarissima prima versione della carta.

Bibliografia

P. A. Frutaz, Le carte del Lazio, XXXI; Diego Gallinelli, Trasformazioni dell’uso e della copertura del suolo, dinamiche territoriali e ricostruzioni Gis nei possedimenti pontini della famiglia Caetani, Tesi di laurea, Università Roma Tre, Anno Accademico, 2019-2020, pp. 123-125.

Cornelis Janszoon Meijer (Amsterdam, 14 gennaio 1629 – Roma, 23 agosto 1701)

|

Cornelis Meyer was a Dutch architect and engineer who worked mainly in Rome and is best known for his innovations in hydraulics. There is little documentation of Meyer’s life in Amsterdam before he moved to Venice in 1674. Venice was a popular destination for Dutch engineers seeking employment, and it was there that Meyer first proposed hydraulic constructions as solutions to problems with the rivers and harbors. Some of these proposals were adopted, and Meyer eventually obtained the official title of engineer. However, before any of his engineering plans were realized, Meyer left Venice in 1675 and went to Rome, never returning to complete the projects that he had first proposed to the Venetian government.

In Rome, Pope Clement X put Meyer in charge of a major civic project that aimed to protect the Via Flaminia against the flooding of the Tiber river. Meyer replaced the architect Carlo Fontana as head engineer of the project because his plans were less expensive than those proposed by Fontana. Since the Via Flaminia was the main road leading into Rome from the north, through the Porta del Popolo, it was the route most used by pilgrims as they entered the city. Therefore, it was critical to protect the road from the periodic flooding of the nearby Tiber. Meyer constructed a passonata, a row of piles, in the Tiber, which deflected the river’s current away from the Via Flaminia. With this engineering feat, Meyer established himself among the architects and engineers working in Rome during the seventeenth century.

After the success of the passonata, Pope Clement X hired Meyer to engineer better navigation on the Tiber for the purpose of increased commerce. Meyer came up with revolutionary solutions to expedite travel along the Tiber and, with the help of artist Gaspar van Wittel, he published his ideas in a book entitled L’arte di restituire a Roma la tralasciata navigatione del suo Tevere in 1683.

L’arte di restituire... was published in three parts and contained Meyer’s plans for the Tiber River, illustrated with etchings of his own as well as those of Giovanni Battista Falda, Gaspar van Wittel, Jacques Blondeau, Barend de Bailiu, Balthasar Denner, Gomarus Wouters, Johannes Collin, and Io. Bat. Honoratus. The book was both a record of Meyer’s engineering skills and feats as well as a form of visual self-promotion for an engineer seeking further commissions. In addition to its artistic quality and professional function, Meyer’s book indicated a new engineering and architectural milieu that Rome had entered by the end of the seventeenth century. A manuscript of Meyer's writing with van Wittel's drawing for Mayer is in the collection of the Biblioteca dell'Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana (34.K.16 (Cors. 1227).

During his lifetime, Meyer published several other books including Nuovi Ritrovimenti (1689) and L’arte di rendere i fiumi navigabili in varii modi, con alter nuove inventioni a varii altri secreti, divisa in tre parte (1689). However, it was with his designs in L’arte di restituire... that Meyer was able to insinuate himself into the artistic and scientific elite in Rome. Upon his death in 1701, he bequeathed his plans and projects in Rome to his son, Otto Meyer.

|

Cornelis Janszoon Meijer (Amsterdam, 14 gennaio 1629 – Roma, 23 agosto 1701)

|

Cornelis Meyer was a Dutch architect and engineer who worked mainly in Rome and is best known for his innovations in hydraulics. There is little documentation of Meyer’s life in Amsterdam before he moved to Venice in 1674. Venice was a popular destination for Dutch engineers seeking employment, and it was there that Meyer first proposed hydraulic constructions as solutions to problems with the rivers and harbors. Some of these proposals were adopted, and Meyer eventually obtained the official title of engineer. However, before any of his engineering plans were realized, Meyer left Venice in 1675 and went to Rome, never returning to complete the projects that he had first proposed to the Venetian government.

In Rome, Pope Clement X put Meyer in charge of a major civic project that aimed to protect the Via Flaminia against the flooding of the Tiber river. Meyer replaced the architect Carlo Fontana as head engineer of the project because his plans were less expensive than those proposed by Fontana. Since the Via Flaminia was the main road leading into Rome from the north, through the Porta del Popolo, it was the route most used by pilgrims as they entered the city. Therefore, it was critical to protect the road from the periodic flooding of the nearby Tiber. Meyer constructed a passonata, a row of piles, in the Tiber, which deflected the river’s current away from the Via Flaminia. With this engineering feat, Meyer established himself among the architects and engineers working in Rome during the seventeenth century.

After the success of the passonata, Pope Clement X hired Meyer to engineer better navigation on the Tiber for the purpose of increased commerce. Meyer came up with revolutionary solutions to expedite travel along the Tiber and, with the help of artist Gaspar van Wittel, he published his ideas in a book entitled L’arte di restituire a Roma la tralasciata navigatione del suo Tevere in 1683.

L’arte di restituire... was published in three parts and contained Meyer’s plans for the Tiber River, illustrated with etchings of his own as well as those of Giovanni Battista Falda, Gaspar van Wittel, Jacques Blondeau, Barend de Bailiu, Balthasar Denner, Gomarus Wouters, Johannes Collin, and Io. Bat. Honoratus. The book was both a record of Meyer’s engineering skills and feats as well as a form of visual self-promotion for an engineer seeking further commissions. In addition to its artistic quality and professional function, Meyer’s book indicated a new engineering and architectural milieu that Rome had entered by the end of the seventeenth century. A manuscript of Meyer's writing with van Wittel's drawing for Mayer is in the collection of the Biblioteca dell'Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei e Corsiniana (34.K.16 (Cors. 1227).

During his lifetime, Meyer published several other books including Nuovi Ritrovimenti (1689) and L’arte di rendere i fiumi navigabili in varii modi, con alter nuove inventioni a varii altri secreti, divisa in tre parte (1689). However, it was with his designs in L’arte di restituire... that Meyer was able to insinuate himself into the artistic and scientific elite in Rome. Upon his death in 1701, he bequeathed his plans and projects in Rome to his son, Otto Meyer.

|