| Reference: | S30324 |

| Author | Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) |

| Year: | 1570 ca. |

| Zone: | Florence |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 441 x 315 mm |

| Reference: | S30324 |

| Author | Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) |

| Year: | 1570 ca. |

| Zone: | Florence |

| Printed: | Rome |

| Measures: | 441 x 315 mm |

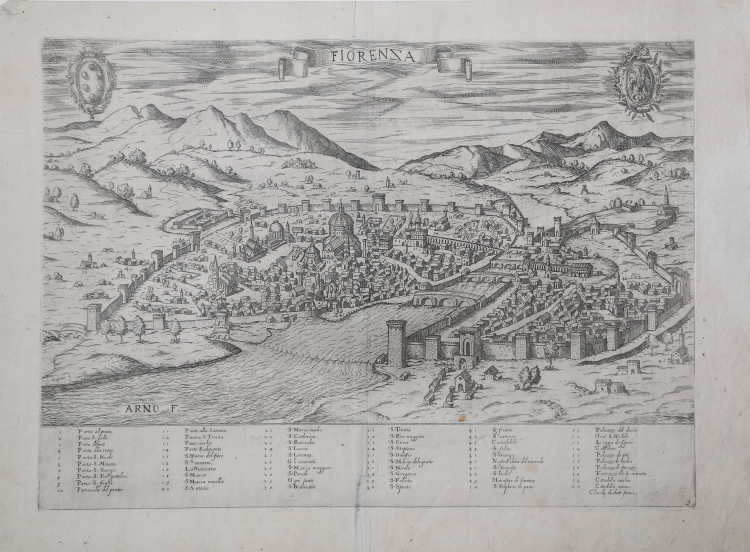

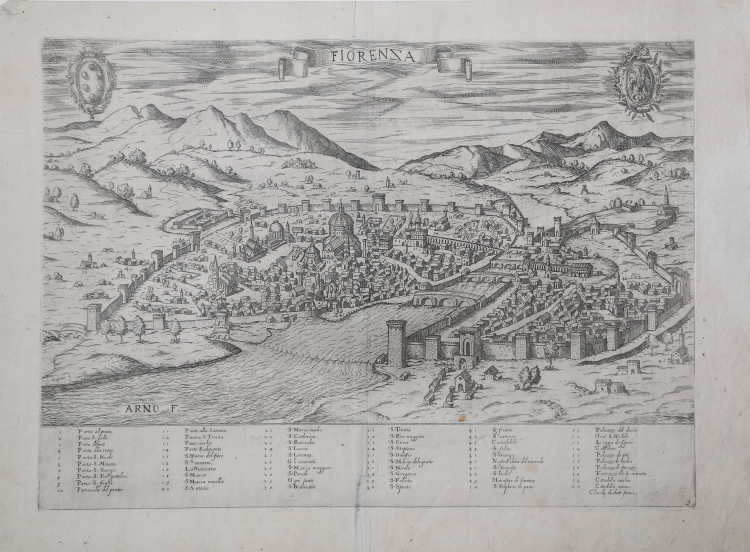

In the upper center, in a ribbon-shaped cartouche, we find the title: FIORENZA. On the upper left is the Medici family coat of arms, on the right that of the city. Along the lower margin is a numerical legend of 60 references to notable places and monuments, spread over six columns. The editorial imprint Claudij duchetti formis follows. Work lacking orientation and graphic scale.

Perspective view of the city, early Roman derivation of Francesco Rosselli's model and Lucantonio degli Uberti's replica, better known as the Veduta della Catena.

The so-called Veduta della Catena [View of the Chain ] is the first known representation of an entire city, the result not of an imaginative projection but of a construction that, based on direct observation from life, also makes use of perspective. This large woodcut, as Hülsen has shown, is derived from the original copperplate engraving, on six copperplates, attributed to Francesco Rosselli, only a fragment of which is now preserved, depicting the countryside in the direction of Fiesole. The woodcut copy, already attributed by Kristeller to Luca Antonio degli Uberti, is preserved in the Prints Cabinet in Berlin. The woodcut in all likelihood was made in the first decade of the 16th century in Venice, as indicated by the parallel line hatching in the shadow areas, which is only used in the first decade of the 16th century. The recently identified paper watermark was used in Venice in 1494-95 and in Syracuse around 1529 (Briquet 2537,2546). Compared to the Florentine model, Lucantonio degli Uberti introduces two innovative elements: the figure of the artist-drawer, bottom right, and the decorative motif of the chain, closed in the upper left by a padlock - hence the name Veduta della Catena - for which different interpretations have been given. The main vantage point is from the southwest, at the bell tower of the Church of Monte Oliveto, and has been elevated to give greater legibility to the architectural features and urban fabric. In the view, the central vertical axis is made to coincide with the axis of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, which, a religious and civic symbol of the city, thus becomes the main element and constant point of reference in the representation of the city itself.

The view creates a continuous spatial field that not only shows the buildings, but also the open spaces, squares, and even the course of the newly constructed streets, and not yet enclosed by the buildings that will be built along their sides. The city's monuments are thus arranged in the plan to reflect the real relationships between them. Outside the city walls, the image restores the main features of the natural landscape: viewed from the southeast, the plan shows the city bounded on the north by the natural wall of the Appenines; the Mugnone valley, through which the road connecting the city to Bologna passes, creates a spectacular opening between the mountains in the upper left corner. Fiesole and S. Domenico are represented with a group of buildings topped by the place name.

The convent of S. Miniato and S. Francesco mark the peaks overlooking the city from the south. The Arno River crosses the image diagonally, cutting the city into two parts. So, the representation of the landscape is neither evocative nor poetic. This seamless representation between the city, the focus of the image, and the landscape responds both to political reality, as the territories represented actually belong to the Florentine state, and to a pictorial ambition: both the city and the surrounding landscape are conceived as a unified topographic space. The view bears the title FIORENZA, a poetic variant of the toponym that, as David Friedman points out, alludes to the concepts of "flower" and "bloom" and is used with celebratory intent, linked to the concepts of peace and prosperity” (cfr. Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e topografia italiana del XVI secolo, pp. 2149-2151 for the Veduta della Catena di Lucantonio degli Uberti).

It is more likely that Duchetti replicates the view attributed to Paolo Forlani (1567), enlarging it and repeating the errors and deformations in the monuments. In the center, a ribbon cartouche with the title; in the left corner, a shield with the Medici coat of arms; on the right, a shield with the Florentine lily. Both Tooley and Marcel Destombes, in their research works on 16th-century Italian cartography, confuse the inscription "Mugnone f.," which identifies the name of the river, with the name of the engraver of the plate, to whom it is erroneously attributed.

Example in the first state of four, before the Giovanni Orlandi's imprint.

"The plate was inherited by Giacomo Gherardi and is included in the catalog edited on behalf of his widow Quintilia Lucidi, dated October 17-19, 1598 (no. 349 described as "Fiorenza in uno foglio reale"). It was then acquired, in 1602, by Giovanni Orlandi who reprinted it unaltered with only the addition of his own imprint. In 1614, when Orlandi moved to Naples, the matrix was given to Hendrick van Schoel, whose print run, however, still bears the date 1602. In the catalog of the Flemish printer, compiled on July 27, 1622 after the publisher's death, the cartographic works described under one heading: “Cosmografia pezzi numero 80.ottanta”. The plates were later sold to Francesco de Paoli, as documented in the inventory of the sale dated November 2, 1633. Possible then the existence of a further issue of the plate, of which, however, we have found no examples" (cf. Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e topografia italiana del XVI secolo, pp. 2156-2157).

Etching and engraving, circa 1570, impressed on contemporary laid virgin paper with margins, small, restored tear in lower center, otherwise in very good condition. Rare.

Bibliografia

Bifolco-Ronca, Cartografia e topografia italiana del XVI secolo, pp. 2156-2157, tav. 1099, I/IV; Cartografia Rara (1986): n. 48; Destombes (1970): n. 70; Ganado (1994): VI, n. 107 & p. 212, n. 47; Benevolo (1969): pp. 56-61, tav. VI; Mori-Boffito (1926): pp. 39, 53; Pagani (2012): p. 82; Tooley (1939): n. 206.

Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) (Attivo a Roma nella seconda metà del XVI sec.))

|

Print dealer and publisher.Active in Venice 1565-1572 and Rome.He was the brother of Francesco Duchetti and a nephew of Antonio Lafrery, inheriting half his plates.

Died 5 December 1585.He was buried in San Luigi dei Francesi.By the terms of his will, his brother –in-law Giacomo Gherardi was to run the business until the majority of Claudio’s son, Claudio.

While Gherardi in charge, he was to inscribe the prints ‘haeredes Claudii Duchetti’.

He commissioned plates from among others Perret, Thomassin and Brambilla.

The name 'Lafreri-School' is a widely used, but rather inaccurate, term used to describe a loose grouping of cartographers, mapmakers, engravers and publishers working in the twin centres of Rome and Venice, from about 1544 to circa 1585. Earlier this century, George Beans, a prominent American collector of Italian maps and atlases, proposed the alternative name 'I.A.T.O.' to describe the composite collections assembled and sold by this school - 'Italian, Assembled-To-Order'. While more apposite, it has failed to catch on with modern cataloguers and collectors. For the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to the cartographers, engravers and publishers involved as "the school", although even this term implies a greater structure and organisation than can currently be established. The principal reference source on the work of the school is R.V. Tooley's Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century (1). In his study, published in 1939, Tooley listed some 614 maps and plates (with variant states counted separately). Some were described from personal examination, others noted from secondary sources and listings. While now much out-dated, as more recent regional carto-bibliographies have effectively superceded particular sections, and new collections have come to light, it remains the only overview of the output of the school. The principal cartographer of the school was Giacomo Gastaldi (fl. 1542-1565), a Piedmontese who worked in Venice, becoming Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic. Karrow described him as "one of the most important cartographers of the sixteenth century. He was certainly the greatest Italian mapmaker of his age..." (2). While his achievement is obvious, it is hard to quantify. A large number of maps were published throughout this period with the geography credited to Gastaldi, but it is often difficult to know what role Gastaldi played in their creation. As a practice, he did not sign himself as publisher, although his name may be found in the title, dedication, or text to the reader. Frequently where there is no imprint one may assume that Gastaldi was the publisher. A further clue may be that many of the maps attributable to Gastaldi as publisher seem to have been engraved by Fabius Licinius. In other cases, where publication is credited to another, it is not always certain whether Gastaldi was commissioned by the publisher to compile the map, whether another less-enterprising publisher merely copied his work and attribution, or simply added Gastaldi's name in the title to add authority to the delineation. His name clearly commanded the same sort of respect that the Sanson name had in the last years of the seventeenth century, and as Guillaume de l'Isle's had in the first half of the eighteenth century. Paolo Forlani was a cartographer and engraver who worked in Venice between 1560 and circa 1571. The majority of his output was published under the imprint of other publishers, such as Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Ferrando Bertelli and Bolognini Zaltieri. In a pioneering study, David Woodward (4), by identifying Forlani's engraving style through various stages of development, has attributed a large number of previously unidentified maps to his hand, and provided a clearer picture of some of the publishing arrangements of the period. In the early 1560s Giovanni Francesco Camocio published a number of maps that were drawn by Forlani, including maps of the World, North Atlantic, Africa, France, Switzerland, and provinces of the Low Countries, to note but a few. Circa 1570, Camocio published an Isolario, or collection of maps of islands, principally from the Mediterranean, but including the British Isles and Iceland. Camocio's earliest issues lacked a title-page, and tended to be a relatively random selection from the available stock. Later he added a title Isole Famose Porti, Fortezze E Terre Maritime. After his death, which is assumed to have been in 1573, the plates were reprinted, with a title-page bearing the Bertelli family address 'alla Libraria del Segno di S. Marco', possibly by Donato Bertelli, whose imprint is found on a later state of Camocio's world map of 1560. The largest grouping was the Bertelli family. The most active was Ferrando Bertelli, who flourished in the 1560's and 1570's, but maps from the last quarter of the seventeenth century are known with the imprints of Andrea, Donato, Lucca, Nicolo and Pietro. Again, a number of maps published by Ferrando were drawn or engraved by Forlani.

Antonio Salamanca (1500 – 1562) settled in Rome his chalcographical business; his activity was then carried on and enlarged by his scholar Antonio Lafrery (1512 – 1577), and then by his grand son Claudio Duchet (Duchetti), Giovanni Orlandi, Henrik van Schoel, and finally by De Rossi. In Venice, the most important centre of map production, he was initiated into engraving by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore and Matteo Pagano, who had worked with Giacomo Gastaldi, the most important European cartographer of the XVI century. Other important exponents of the Venetian chalcography were Fabio Licinio, Fernando Bertelli, Giovanni Francesco Camocio and above all of them Paolo Forlani. Although he’s better known as publisher of Roman archeology, Antoine de Lafrery, born in France, has been the publisher thathas given the biggest impulse to Roman chalcography, becoming in a few years an expert seller as well. For that reason, even though he’s not the one that has published most maps in his time, all the chalcographic works printed in Rome and Venice during the XVI century are nowadays defined as “charts of lafrerian school”. This definition was given by Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, one of the fathers of the history of cartography, who also introduced the definition of Lafrery Atlas, talking about charts printed in Rome and published by Lafrery, in which we find a sort of title page with the title Tavole moderne de geografia secondo l’ordine di Tolomeo. Lafrery’s school produced a huge amount of maps, usually selling them as separate charts and somehow and then edited in a bigger volume. Since the charts had all different measures, the artists needed to trim them with copper to get them to the same size, adding at the end estra pieces of paper, if necessary.

|

Claudio DUCHET (Duchetti) (Attivo a Roma nella seconda metà del XVI sec.))

|

Print dealer and publisher.Active in Venice 1565-1572 and Rome.He was the brother of Francesco Duchetti and a nephew of Antonio Lafrery, inheriting half his plates.

Died 5 December 1585.He was buried in San Luigi dei Francesi.By the terms of his will, his brother –in-law Giacomo Gherardi was to run the business until the majority of Claudio’s son, Claudio.

While Gherardi in charge, he was to inscribe the prints ‘haeredes Claudii Duchetti’.

He commissioned plates from among others Perret, Thomassin and Brambilla.

The name 'Lafreri-School' is a widely used, but rather inaccurate, term used to describe a loose grouping of cartographers, mapmakers, engravers and publishers working in the twin centres of Rome and Venice, from about 1544 to circa 1585. Earlier this century, George Beans, a prominent American collector of Italian maps and atlases, proposed the alternative name 'I.A.T.O.' to describe the composite collections assembled and sold by this school - 'Italian, Assembled-To-Order'. While more apposite, it has failed to catch on with modern cataloguers and collectors. For the purposes of this article, I intend to refer to the cartographers, engravers and publishers involved as "the school", although even this term implies a greater structure and organisation than can currently be established. The principal reference source on the work of the school is R.V. Tooley's Maps in Italian Atlases of the Sixteenth Century (1). In his study, published in 1939, Tooley listed some 614 maps and plates (with variant states counted separately). Some were described from personal examination, others noted from secondary sources and listings. While now much out-dated, as more recent regional carto-bibliographies have effectively superceded particular sections, and new collections have come to light, it remains the only overview of the output of the school. The principal cartographer of the school was Giacomo Gastaldi (fl. 1542-1565), a Piedmontese who worked in Venice, becoming Cosmographer to the Venetian Republic. Karrow described him as "one of the most important cartographers of the sixteenth century. He was certainly the greatest Italian mapmaker of his age..." (2). While his achievement is obvious, it is hard to quantify. A large number of maps were published throughout this period with the geography credited to Gastaldi, but it is often difficult to know what role Gastaldi played in their creation. As a practice, he did not sign himself as publisher, although his name may be found in the title, dedication, or text to the reader. Frequently where there is no imprint one may assume that Gastaldi was the publisher. A further clue may be that many of the maps attributable to Gastaldi as publisher seem to have been engraved by Fabius Licinius. In other cases, where publication is credited to another, it is not always certain whether Gastaldi was commissioned by the publisher to compile the map, whether another less-enterprising publisher merely copied his work and attribution, or simply added Gastaldi's name in the title to add authority to the delineation. His name clearly commanded the same sort of respect that the Sanson name had in the last years of the seventeenth century, and as Guillaume de l'Isle's had in the first half of the eighteenth century. Paolo Forlani was a cartographer and engraver who worked in Venice between 1560 and circa 1571. The majority of his output was published under the imprint of other publishers, such as Giovanni Francesco Camocio, Ferrando Bertelli and Bolognini Zaltieri. In a pioneering study, David Woodward (4), by identifying Forlani's engraving style through various stages of development, has attributed a large number of previously unidentified maps to his hand, and provided a clearer picture of some of the publishing arrangements of the period. In the early 1560s Giovanni Francesco Camocio published a number of maps that were drawn by Forlani, including maps of the World, North Atlantic, Africa, France, Switzerland, and provinces of the Low Countries, to note but a few. Circa 1570, Camocio published an Isolario, or collection of maps of islands, principally from the Mediterranean, but including the British Isles and Iceland. Camocio's earliest issues lacked a title-page, and tended to be a relatively random selection from the available stock. Later he added a title Isole Famose Porti, Fortezze E Terre Maritime. After his death, which is assumed to have been in 1573, the plates were reprinted, with a title-page bearing the Bertelli family address 'alla Libraria del Segno di S. Marco', possibly by Donato Bertelli, whose imprint is found on a later state of Camocio's world map of 1560. The largest grouping was the Bertelli family. The most active was Ferrando Bertelli, who flourished in the 1560's and 1570's, but maps from the last quarter of the seventeenth century are known with the imprints of Andrea, Donato, Lucca, Nicolo and Pietro. Again, a number of maps published by Ferrando were drawn or engraved by Forlani.

Antonio Salamanca (1500 – 1562) settled in Rome his chalcographical business; his activity was then carried on and enlarged by his scholar Antonio Lafrery (1512 – 1577), and then by his grand son Claudio Duchet (Duchetti), Giovanni Orlandi, Henrik van Schoel, and finally by De Rossi. In Venice, the most important centre of map production, he was initiated into engraving by Giovanni Andrea Vavassore and Matteo Pagano, who had worked with Giacomo Gastaldi, the most important European cartographer of the XVI century. Other important exponents of the Venetian chalcography were Fabio Licinio, Fernando Bertelli, Giovanni Francesco Camocio and above all of them Paolo Forlani. Although he’s better known as publisher of Roman archeology, Antoine de Lafrery, born in France, has been the publisher thathas given the biggest impulse to Roman chalcography, becoming in a few years an expert seller as well. For that reason, even though he’s not the one that has published most maps in his time, all the chalcographic works printed in Rome and Venice during the XVI century are nowadays defined as “charts of lafrerian school”. This definition was given by Adolf Erik Nordenskiold, one of the fathers of the history of cartography, who also introduced the definition of Lafrery Atlas, talking about charts printed in Rome and published by Lafrery, in which we find a sort of title page with the title Tavole moderne de geografia secondo l’ordine di Tolomeo. Lafrery’s school produced a huge amount of maps, usually selling them as separate charts and somehow and then edited in a bigger volume. Since the charts had all different measures, the artists needed to trim them with copper to get them to the same size, adding at the end estra pieces of paper, if necessary.

|