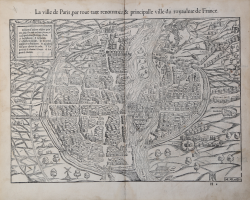

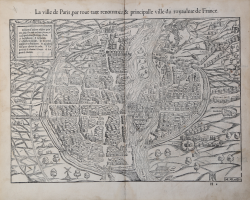

| Reference: | S48015 |

| Author | Sebastian Münster |

| Year: | 1552 |

| Zone: | Paris |

| Printed: | Basle |

| Measures: | 390 x 315 mm |

| Reference: | S48015 |

| Author | Sebastian Münster |

| Year: | 1552 |

| Zone: | Paris |

| Printed: | Basle |

| Measures: | 390 x 315 mm |

Early map of Paris taken from the Cosmographiae Universalis, Frenche edition, published with the title La cosmographie universelle, contenant la situation de toutes les parties du monde Basel, 1552 [first French edition].

“Le plan qui figure à partir de 1550 dans la Cosmographie de Sébastien Münster (édition prinsceps a Bâle en 1544, en allemand, chez Heinrich Petri) parait la même année dans les éditions latine et allemande (Bâle, 1550), puis française (Bâle, 1552), enfin italienne (Bâle, 1558). A partir des éditions latine et allemande de 1572, l'éditeur utilise une gravure différente, quoique très proche de l'original, dont il reprend le bois à un imprimeur lyonnais, Jean d'Ogerolles

Remarquons toutefois que la troisième et dernière édition italienne de la Cosmographie, publiée à Cologne en 1575, conserve la gravure de l'édition de 1550: l'abandon de cette première représentation par l'éditeur balois n'est donc pas la conséquence d'une perte ou d'une usure du bois original.

Selon le texte imprimé au dos, le plan de la ville de Paris est représenté secundum situm et figuram quam habuit hoc Christi anno 1548. Au siècle dernier, Bonnardot, puis Franklin, avaient noté les difficultés topographiques de cette date; le plan figure en effet les portes de l'enceinte de Philippe-Auguste, démolies entre 1529 et 1535, la tour de Billy, détruite par la foudre en juillet 1538; l'existence sur le plan du collegium regium, fondé par François Ir en 1529, en suggérant un terminum a quo, permet de proposer la date de 1530 environ pour l'état représenté de la ville.

La date de 1548 est vraisemblablement celle de l'envoi à Münster du document topographique; une douzaine d'autres vues, contenues dans la Cosmographie, sont en effet datées 1546 (Francfort-sur-le-Main), 1548 (Trêves, Rufach, Cologne, Vienne, Francfort-sur- l'Oder), 1549 pour la majorité (Berne, Bâle, Spire, Coblence, Fribourg, Nördlingen, théâtre de Vérone, Rome); ces dates correspondent à la période durant laquelle Münster a recueilli la documentation carto- graphique et iconographique nécessaire à l'édition illustrée de sa Cosmographie; le texte précise ainsi, dans quelques cas, l'auteur de l'envoi - pour Rufach, Anton Kurtzius, gouverneur de la ville, voire sa date: le plan de Trêves a été envoyé par l'archevêque de la ville en novembre 1548 (date portée aussi au verso du plan, comme dans le cas de Paris), celui de Vienne en août 1547 (daté 1548) par le médecin et historien Wolfgang Lazius (1514-1565), qui venait de publier son Viennae-Austriae, rerum Viennensium commentarii in quatuor libri distincti..., Bâle, J. Oporini, 1546. La date 1548, portée au dos du plan de Paris, n'est donc pas celle d'un quelconque lever topographique - à suivre J. Dérens, le plan de Münster est la copie d'une réduction gravée vers 1530 du grand plan manuscrit levé entre 1523 et 1530 dont l'original est perdu, mais selon toute vraisemblance, celle de l'envoi, à Münster, par une personne de nous inconnue du document topographique qu'il avait demandé. Le plan de la Cosmographie embrasse un champ assez vaste, à l'est, jusqu'à l'abbaye Saint-Antoine et au fau- bourg Saint-Marcel, au nord, jusqu'à Montmartre et au gibet de Montfaucon, à l'ouest, jusqu'au faubourg Saint-Honoré et au gibet de Saint-Germain-des-Prés, au sud, enfin, jusqu'au moulin des Gobelins et aux Cordelières de la rue de Lourcine. De tous les plans du xvr° siècle, il livre l'état topographique le plus ancien de ce que Dumolin a appelé la famille du plan de la Tapisserie . Il est, d'autre part, le plus ancien plan de Paris que nous possédons actuellement, après la disparition de la Gouache en 1871. Le vif débat qui a opposé, à la fin du xix siècle, les érudits autour de l'antériorité du plan de Münster ou du plan d'Arnoullet s'est en effet clos en faveur de celui de Münster les arguments de l'abbé Dufour, l'un des décou- vreurs du plan d'Arnoullet qu'ignorait Bonnardot -, ont été réfutés par G. Marcel, qui les estime tous les deux copiés sur un même original jusqu'ici perdu. M. Pastoureau (p. 225) a récemment confirmé l'antériorité du plan de Münster en remarquant qu'Arnoullet a copié au moins 12 planches de son Épitome (Lyon, 1553) sur la Cosmographie de Münster.

Bien que figurant dans seize éditions successives de la Cosmographie, le plan initial n'a connu aucune modification; à une seule exception: l'identification topоnymique Cordelières (en haut, à droite du plan, dans le faubourg Saint-Marcel), qui figure sur le plan de l'édition latine de 1550 pour désigner le couvent des Cordelières de la rue de Lourcine, est tranformée, à tort, en Cordeliers dès l'édition allemande de 1550. Quelle que soit la langue du texte, les indications topographiques sur le plan sont en latin” (cfr. Jean Boutier, Les Plans de Paris des origins (1493) à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, pp. 78-79).

The Cosmographiae Universalis of Sebastian Münster (1488-1552), printed for the first time in Basel in 1544 by the publisher Heinrich Petri, was updated several times and increased with new maps and urban representations in its many editions until the beginning of the next century. Münster had worked to collect information in order to obtain a work that did not disappoint expectations and, after a further publication in German embellished with 910 woodblock prints, arrived in 1550 to the final edition in Latin, illustrated by 970 woodcuts.

There were then numerous editions in different languages, including Latin, French, Italian, English and Czech. After his death in Münster (1552), Heinrich Petri first, and then his son Sebastian, continued the publication of the work. The Cosmographia universalis was one of the most popular and successful books of the 16th century, and saw as many as 24 editions in 100 years: the last German edition was published in 1628, long after the author's death. The Cosmographia contained not only the latest maps and views of all the most famous cities, but also a series of encyclopedic details related to the known, and unknown, world.

The particular commercial success of this work was due in part to the beautiful engravings (among whose authors can be mentioned Hans Holbein the Younger, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, David Kandel).

Woodcut, signed with the monogram HR MD at lower right [Hans Rudolph Manuel], very good condition.

Bibliografia

Jean Boutier, Les Plans de Paris des origins (1493) à la fin du XVIIIe siècle, pp. 78-81, 5.III.

Sebastian Münster (1488 - 1552)

|

Sebastian Münster was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and Hebrew scholar whose Cosmographia (1544; "Cosmography") was the earliest German description of the world and a major work - after the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 - in the revival of geography in the 16th-century Europe. Altogether, about 40 editions of the Cosmographia appeared during 1544-1628. Although other cosmographies predate Münster's, he is given first place in historical discussions of this sort of publication, and was a major influence on his subject for over 200 years.

In nearly all works by Münster, his Cosmographia is given pride of place. Despite this, we still lack a detailed survey of its contents from edition to edition, along the years from 1544 to 1628, and an account of its influence on a wide range of scientific disciplines. Münster obtained the material for his book in three ways. He used all available literary sources. He tried to obtain original manuscript material for description of the countryside and of villages and towns. Finally, he obtained further material on his travels (primarily in south-west Germany, Switzerland, and Alsace). The Cosmographia contained not only the latest maps and views of many well-known cities, but included an encyclopaedic amount of details about the known - and unknown - world and undoubtedly must have been one of the most widely read books of its time.

Aside from the well-known maps and views present in the Cosmographia, the text is thickly sprinkled with vigorous woodcuts: portraits of kings and princes, costumes and occupations, habits and customs, flora and fauna, monsters and horrors. The 1614 and 1628 editions of Cosmographia are divided into nine books. Nearly all the sections, especially those dealing with history, were enlarged. Descriptions were extended, additional places included, errors rectified.

|

Sebastian Münster (1488 - 1552)

|

Sebastian Münster was a German cartographer, cosmographer, and Hebrew scholar whose Cosmographia (1544; "Cosmography") was the earliest German description of the world and a major work - after the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 - in the revival of geography in the 16th-century Europe. Altogether, about 40 editions of the Cosmographia appeared during 1544-1628. Although other cosmographies predate Münster's, he is given first place in historical discussions of this sort of publication, and was a major influence on his subject for over 200 years.

In nearly all works by Münster, his Cosmographia is given pride of place. Despite this, we still lack a detailed survey of its contents from edition to edition, along the years from 1544 to 1628, and an account of its influence on a wide range of scientific disciplines. Münster obtained the material for his book in three ways. He used all available literary sources. He tried to obtain original manuscript material for description of the countryside and of villages and towns. Finally, he obtained further material on his travels (primarily in south-west Germany, Switzerland, and Alsace). The Cosmographia contained not only the latest maps and views of many well-known cities, but included an encyclopaedic amount of details about the known - and unknown - world and undoubtedly must have been one of the most widely read books of its time.

Aside from the well-known maps and views present in the Cosmographia, the text is thickly sprinkled with vigorous woodcuts: portraits of kings and princes, costumes and occupations, habits and customs, flora and fauna, monsters and horrors. The 1614 and 1628 editions of Cosmographia are divided into nine books. Nearly all the sections, especially those dealing with history, were enlarged. Descriptions were extended, additional places included, errors rectified.

|