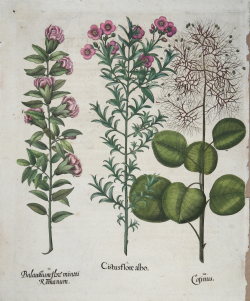

| Reference: | S2070 |

| Author | Basilius BESLER |

| Year: | 1613 |

| Printed: | Amsterdam |

| Measures: | 392 x 485 mm |

| Reference: | S2070 |

| Author | Basilius BESLER |

| Year: | 1613 |

| Printed: | Amsterdam |

| Measures: | 392 x 485 mm |

Etching with later hand colour. Folio prints listed from a special edition of the work entitled Hortus Eystettensis: Bishop's Garden by Basilius Besler, a pharmacist and botanist, published in 1613.

Johann Konrad von Gemmingen, Prince Bishop of Eichstätt, Germany, arranged a magnificent garden to encircle his castle. This garden was one of the first of its kind, an inclusive display of shrubs and flowering plants, mostly European, but with some from Asia, Africa and the Americas.

The Prince commissioned this marvelous botanical book to be made, which chronicles the garden through the four seasons, with most of the plants depicted actual size. A team of at least ten engravers worked under Besler on this massive project for 16 years, translating in situ and specimen drawings faithfully to copperplates.

On 367 folio size plates over 1000 flowers representing 667 species are depicted.

Published in an edition of 300 in 1613, Hortus Eysttensis is a landmark work in the history of botanical art and considered one of the greatest botanical books ever created.

Copperplate with fine later hand colour, very good condition.

Basilius BESLER (Wöhrd 1561 - 1629)

|

Basilius Besler was an esteemed Nuremburg apothecary, chemist, healer, and botanist. He spent a good part of his life caring for the garden of the Archbishopric of Eichstätt in Bavaria. Bishop Johann Konrad von Gemmingen was an avid botanist and formed his episcopal garden at Eichstätt to celebrate the diversity of creation. Around 1600, the bishop commissioned Besler to create a work describing the plants cultivated in that splendid botanical garden, and Besler labored over the next sixteen years on the project. He was assisted by his physician brother and by a team of excellent German draftsmen and engravers, including Wolfgang Kilian of Augsburg. The result was the Hortus Eystettensis (Garden of Eichstätt), now more simply known as the Florilegium. Previous Medieval and Renaissance botanicals had focussed on herbs with medicinal or culinary uses, often portrayed in a fairly simple, workman-like manner. Their images were generally adequate for rough plant-identification, but made no pretensions of being artistic in their own right. The Hortus changed that. Its images were of flowers, herbs, vegetables, ornamental plants, exotic plants such as tobacco and peppers. All were portrayed life-sized, so some were quite large. The compostion within each page was stylish and eye-catching, and when hand-coloring was added, the effect was - and still is - visually stunning, with “quality, richness of detail, subtleties, vividness of color and luster.” Published in 1613 in imperial folio format, it consisted of 367 copper engravings, with the plants generally grouped on their pages, so many plates contained two, three or more individual plants to depict a total of 1084 plants. The basic division of the Hortus corresponds to the four seasons, progressing as dictated by the plants themselves - flowering, then fruiting - an embryonic system of classification based on the biological rhythms of plants in nature. The first edition opened in “Winter” with 7 plates showing 28 plants. “Spring” was more abundant with 134 plates depicting 454 plants and “Summer” even more so with 505 plants on 184 plates. The work ended in “Autumn” with 42 plates showing 98 images. Not by chance is the modern French version of the herbal called Herbier des quatres saisons, which is echoed in the 1998 Italian version L'erbario delle quattro stagioni. Latin descriptions were printed on the backs of the images and anticipated some remarkable developments for the beginning of the 17th century, not least of which was the recurrent use of binomial denominations. The Hortus predated the binomial nomenclature made official by Carolus Linnaeus in 1753 and only became the methodological norm at the end of the 18th century. Basilius Besler was portrayed in the frontispiece of the book with a plant in hand (it may be a basil, a nod to his name). The Hortus came out in two other editions (Nuremburg 1640 and 1713) with the same plates, until their iniquitous destruction by Munich’s Royal Mint in 1817. The actual gardens were destroyed by Swedish troops in 1634, but a modern reconstruction of the original garden opened to the public in Eichstätt in 1998. The Hortus Eystettensis inspired by those gardens is still considered one of the grandest and most complete artistic collections of ornamental plants

|

Basilius BESLER (Wöhrd 1561 - 1629)

|

Basilius Besler was an esteemed Nuremburg apothecary, chemist, healer, and botanist. He spent a good part of his life caring for the garden of the Archbishopric of Eichstätt in Bavaria. Bishop Johann Konrad von Gemmingen was an avid botanist and formed his episcopal garden at Eichstätt to celebrate the diversity of creation. Around 1600, the bishop commissioned Besler to create a work describing the plants cultivated in that splendid botanical garden, and Besler labored over the next sixteen years on the project. He was assisted by his physician brother and by a team of excellent German draftsmen and engravers, including Wolfgang Kilian of Augsburg. The result was the Hortus Eystettensis (Garden of Eichstätt), now more simply known as the Florilegium. Previous Medieval and Renaissance botanicals had focussed on herbs with medicinal or culinary uses, often portrayed in a fairly simple, workman-like manner. Their images were generally adequate for rough plant-identification, but made no pretensions of being artistic in their own right. The Hortus changed that. Its images were of flowers, herbs, vegetables, ornamental plants, exotic plants such as tobacco and peppers. All were portrayed life-sized, so some were quite large. The compostion within each page was stylish and eye-catching, and when hand-coloring was added, the effect was - and still is - visually stunning, with “quality, richness of detail, subtleties, vividness of color and luster.” Published in 1613 in imperial folio format, it consisted of 367 copper engravings, with the plants generally grouped on their pages, so many plates contained two, three or more individual plants to depict a total of 1084 plants. The basic division of the Hortus corresponds to the four seasons, progressing as dictated by the plants themselves - flowering, then fruiting - an embryonic system of classification based on the biological rhythms of plants in nature. The first edition opened in “Winter” with 7 plates showing 28 plants. “Spring” was more abundant with 134 plates depicting 454 plants and “Summer” even more so with 505 plants on 184 plates. The work ended in “Autumn” with 42 plates showing 98 images. Not by chance is the modern French version of the herbal called Herbier des quatres saisons, which is echoed in the 1998 Italian version L'erbario delle quattro stagioni. Latin descriptions were printed on the backs of the images and anticipated some remarkable developments for the beginning of the 17th century, not least of which was the recurrent use of binomial denominations. The Hortus predated the binomial nomenclature made official by Carolus Linnaeus in 1753 and only became the methodological norm at the end of the 18th century. Basilius Besler was portrayed in the frontispiece of the book with a plant in hand (it may be a basil, a nod to his name). The Hortus came out in two other editions (Nuremburg 1640 and 1713) with the same plates, until their iniquitous destruction by Munich’s Royal Mint in 1817. The actual gardens were destroyed by Swedish troops in 1634, but a modern reconstruction of the original garden opened to the public in Eichstätt in 1998. The Hortus Eystettensis inspired by those gardens is still considered one of the grandest and most complete artistic collections of ornamental plants

|